There was a time when serious people could have a good-faith debate about how best to weigh the future cost of climate change against the present cost of overhauling the global energy system. Stemming the rise in temperature would not be cheap and it would not be easy, which is why Al Gore called his 2006 film An Inconvenient Truth, because to grasp the sweeping, transformative changes needed to stop catastrophic warming was to be, well, highly inconvenienced.

It was so inconvenient, in fact, that Democrats failed to pass a cap and trade bill in 2009 despite winning the White House and both chambers of Congress. With the economy in shambles, observers intoned, voters had little appetite for a costly climate program. The wave of public concern that emerged after Gore’s film had finally crashed, drowning any hopes of a climate bill.

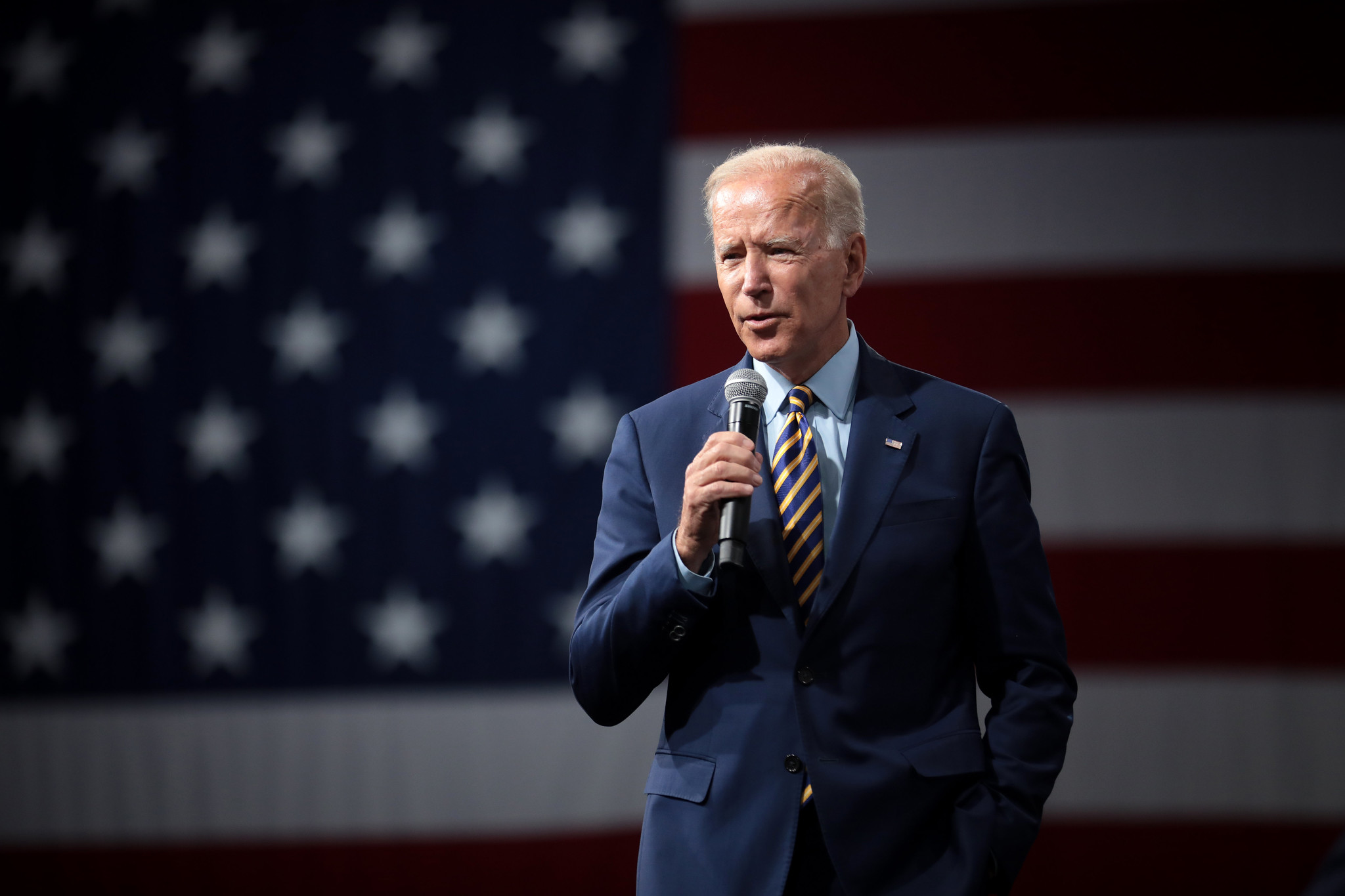

The view that voters don’t care about climate change has persisted in the press ever since. Not once, in 2012 or 2016, did any presidential debate moderator ask about climate change. While moderators pushed candidates on climate in 2020, news reports characterized then-candidate Joe Biden’s pledge to transition away from oil as a “slip” or a “gaffe,” and they focused on the high cost of tackling climate change while failing to mention the deadly price of doing nothing.

To imply that climate change is a political loser is to misapprehend the American public, which is more worried about the climate than ever before. President-elect Biden made the climate crisis a central pillar of his campaign, and he won more votes than any other candidate in history, smashing Barack Obama’s 2008 record to overcome an incumbent president. Over the last decade, the economics and politics of climate change have undergone a radical shift. Biden took note. The press might do the same.

Since 2009, the cost of wind power has dropped 71 percent, while the cost of solar power has dropped 90 percent. Today, new wind and solar installations are as cheap or cheaper than new coal, gas and nuclear plants in most parts of the country. Likewise, since 2010, the cost of EV batteries has dropped 87 percent. Factoring in savings on fuel and repairs, today’s EVs are cheaper over their lifetime than comparable gas-powered cars.

The energy revolution is well underway. It’s just not happening fast enough to stave off the worst of climate change. To meet the goals of the Paris Agreement, we must accelerate this trend. After a decade of plummeting costs, we can do so for a fraction of what the world has already spent on coronavirus relief.

The ascendance of clean energy has happened in tandem with the decline of fossil fuels. Coal, unable to compete with cheaper forms of power, continued its collapse under President Trump, with more than a dozen coal companies declaring bankruptcy since he took office. At the same time, fracking fueled a drilling boom, flooding the market with cheap oil and gas. Drillers struggled to turn a profit and had to survive on debt. Now that the bills are coming due, dozens of companies are going bankrupt.

Facing headwinds, oil and gas giants BP and Shell have made gestures toward moving into renewable energy. ExxonMobil, on the other hand, remains committed to fossil fuels, and Wall Street remains unimpressed. The oil giant was recently booted from the Dow Jones Industrial Average, a sampling of America’s most reliably profitable companies, after 92 years on the index.

As the country considers how to recover from the current economic slump, it has a choice between trying to resuscitate fossil fuels or putting clean energy on steroids. So, it’s worth asking which option would be better for the economy. According to a recent report from the University of Oxford, the answer is clean energy. Renewables are simply more labor-intensive than fossil fuels. You get more jobs for every dollar you spend.

Americans broadly understand this fact. By a more than two-to-one margin, voters say that clean energy is a better source of jobs than fossil fuels. By an even bigger margin, they support Biden’s $2 trillion climate plan.

This isn’t just about jobs, however. Americans are really worried about climate change. Experts at Yale and George Mason University have divided Americans into six segments according to their views on climate change, ranging from the “Alarmed” to the “Dismissive.” In 2015, those two groups were equal in number, but today, the “Alarmed” outnumber the “Dismissive” almost four to one. Even more startling: there are proportionally more “Alarmed” Fox News viewers today than there were “Alarmed” Americans in 2015.

Despite this, the press continues to misjudge the politics of climate change. Political reporters treated Biden’s pledge to wean off oil as an exotic form of political suicide, even though most Americans support phasing out oil. Reporters warned that Biden’s pledge to end new fracking on public lands would hurt him in Pennsylvania, even though most Pennsylvania voters support this very policy. In the end, Biden performed better than Hillary Clinton in eight of the top 10 fracking counties in Pennsylvania.

Turnout was key to Biden’s win. Among his supporters, climate change consistently ranks as a top issue, trailing only health care, the pandemic and racial inequality in a recent poll. Climate may have played a particularly important role with young voters and Latinos, two segments of less reliable voters who are heavily invested in climate change.

In the final week of this campaign, Biden ran two national TV ads on climate change, including one targeting young voters that aired on Comedy Central and Adult Swim. When progressive group MoveOn tested 70 different social media ads aimed at boosting voter turnout, it was a climate ad that performed best, earning particularly high marks with young voters of color. Early estimates suggest these voters turned out in big numbers in 2020, helping deliver Arizona, Georgia and Pennsylvania to Biden.

If Democrats prevail in the Georgia Senate runoff election and gain unified control of government, they will have a shot at passing some version of Biden’s climate plan, but it won’t be easy. They will need to abolish the filibuster and sway centrists like Sen. Joe Manchin (WV) and Sen. Kyrsten Sinema (AZ). If Democrats fail to win the Senate, a climate bill will be nigh impossible.

And yet, this is not 2009. Even in a divided government, the conservative Chamber of Commerce sees hope for an infrastructure bill that deals with climate change. The fossil fuel industry is in decline, and its political power is waning. And new players, like the Sunrise Movement and Justice Democrats, are rewriting the playbook for climate activism.

Most importantly, solving climate change is cheaper, more urgent and more popular than ever before, which is, politically speaking, pretty convenient.

Jeremy Deaton writes for Nexus Media News, a nonprofit climate change news service. You can follow him @deaton_jeremy.