At the start of 2017, just 22 cities had committed to sourcing all of their power from clean energy by 2050. As of this week, that number is 72. Since President Trump moved into the Oval Office and started ripping up federal climate policy, dozens of cities in conservative states have set ambitious goals for clean power, including Salt Lake City, St. Louis and Atlanta. Now for the hard part. These cities must chart a course to reaching their goal.

Atlanta recently laid out three options for hitting 100 percent clean energy. The document reveals two important facts. First, if Atlanta invests in new clean energy projects — as opposed to buying credits for clean energy generated out of state — it will see more jobs, smaller energy bills and less pollution. Second, if Atlanta wants to rely solely on locally sourced renewable power, it will need the help of the state legislature and the public service commission, both of which are controlled by Republicans, many of whom are wary of wind and solar. The proposals speak both to the promise of renewable power and to the limitations of local government. It will be hard to achieve 100 percent clean energy, but as former vice president Al Gore recently said, if Atlanta can do it, anybody can.

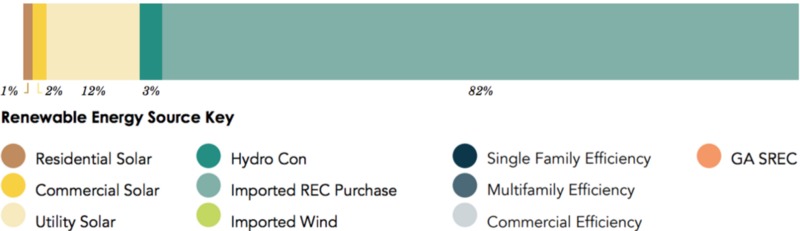

Officials listed the three proposals in increasing order of difficulty. The first calls for buying clean power credits from out-of-state wind farms to make up for power purchased from coal, gas and nuclear power plants. This option could be executed more quickly and cheaply than the other two, but it offers the smallest upside. In this scenario, Atlanta would support the development of clean energy, and thereby stem climate change, but it would not manage to shrink power bills, cut local pollution or create jobs for residents.

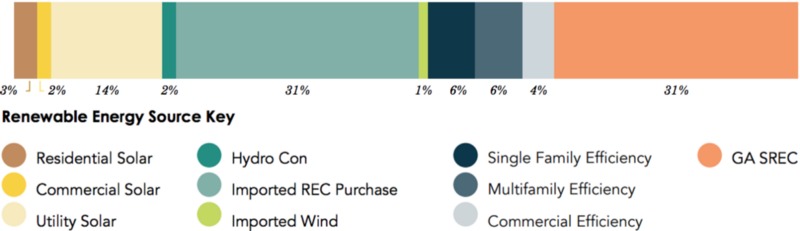

The second option calls for investing in solar energy and energy efficiency. Like the first scenario, it also requires buying clean power credits, some from out-of-state wind farms and some from in-state solar farms — assuming Georgia Power, the local utility, invests in solar power. This scenario boasts the best cost-to-benefit ratio, meaning the greatest savings on electricity and healthcare per dollar spent on clean power.

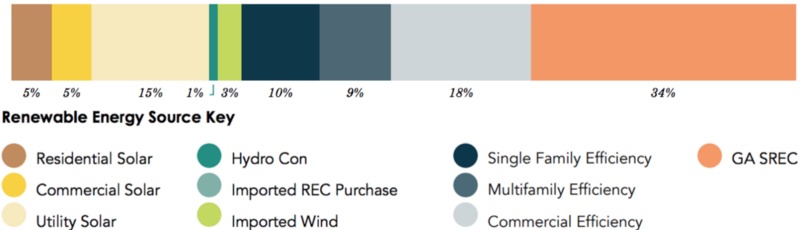

The third option calls for going all in on clean energy, making big investments in rooftop solar arrays and community solar farms, in addition to making buildings more efficient. Even in this scenario, however, the city would rely in part on fossil fuels for power, and it would have to buy solar energy credits to reach its goal.

Overall, this proposal would yield the biggest returns. Officials say this option would create almost 8,000 jobs and produce nearly $12 billion in returns by slashing power bills and cutting pollution, thereby reducing healthcare costs. In this scenario, the city would also save 10 billion gallons of water that would otherwise be used in the operation of coal, gas and nuclear power plants — the largest water savings of any option.

If the officials want to pursue the second or third options, they will need the help of the Georgia Public Service Commission and the state legislature. The Public Service Commission, for example, would need to direct Georgia Power to build enough solar power in Georgia to satisfy Atlanta’s aims, allowing the city to purchase clean energy credits that support local solar projects instead of distant wind projects.

“We recognize that we can’t put all of the renewable energy in the city limits. So that means it’s going to have to come from somewhere else,” said Ted Terry, director of the Georgia chapter of the Sierra Club. “We don’t want to be exporting our dollars to other states. No offense to Oklahoma, but we’ve got the energy resources right here in our state to power our state.” Terry wants to see Atlanta source power from in-state solar arrays, “built by Georgia workers that will add value to the tax base of Georgia.”

The legislature could help by allowing solar owners to sell more of their power back to the grid or by creating a renewable portfolio standard, asserting the state must source a certain portion of its power from wind and solar. Terry said that a renewable portfolio standard is unlikely to pass the Republican-dominated legislature, but a tax credit for solar installations or energy efficiency upgrades just might. “The legislature is very politicized and ideological,” Terry said.

Given the political hurdles, authors of the three proposals warned that trying to achieve 100 percent clean energy by 2035 would likely result in the city “simply purchasing large amounts of renewable energy credits rather than achieving the goal through energy efficiency and in-state renewable generation.” They urged the city council to aim for the more modest date of 2050, which would provide “a realistic timeline in which to achieve an equitable, affordable, and cost-effective 100 percent clean energy future.”

As officials noted, the more power the city can generate locally, the greater the benefits for its poorest residents, who devote up to a 10 percent of their monthly income to electricity costs. “Energy equity was a huge deal — relieving the energy burden for people who are lower income,” Terry said. Officials called for shrinking power bills and funding efficiency upgrades in the homes of low-income families. The right policies could radically cut the cost of power, which would be significant for families struggling to pay rent.

“This is not just a plan drafted in a vacuum at City Hall — our aim is to unlock the potential of Atlantans to take action to make our home more resilient to the shocks and stresses of a warming planet,” wrote Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms in an introductory letter. Bottoms described Atlanta’s plan for clean energy as “a social contract to protect the health and welfare of its citizenry.”

Jeremy Deaton writes for Nexus Media, a syndicated newswire covering climate, energy, policy, art and culture. You can follow him @deaton_jeremy.