It’s fall, and all across America, kids are heading back to school. Gone are the carefree days of summer. Returned are the exams that shape students’ futures— from next year’s course load to college graduation.

While study sessions and tutors are go-to tactics to boost grades, new research is uncovering the impact climate change may have on scholastic performance. Studies show that heat and carbon pollution impair cognition, hamper learning and undermine student achievement. For students and parents, our changing climate is becoming another hurdle on the path to academic success.

Heat drives down test scores.

“My kids are in terrible moods when it’s hot out. They lose their appetite and need to drink significantly more water to stay hydrated,” said Leigh Garofalow, a New Jersey mother of two. “We live where I grew up, and summers were never like this for me.”

July and August tied for the hottest months on record. They are the latest data points in a stretch of history-making heat that will likely render 2016 the warmest year ever recorded.

“My daughter had heat exhaustion two separate times during this summer’s heatwaves,” said Garofalow, who is a member of the Climate Reality Leadership Corps. “She got a headache, nausea and vomited on both occasions. We had to put her in a cool bath and feed her ice to make her feel better.”

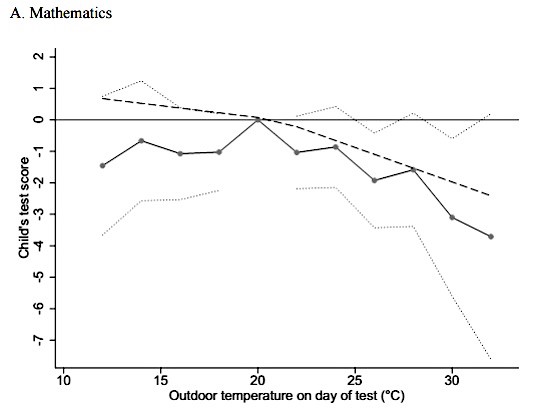

Heatwaves aren’t just fueling headaches and dehydration. They are also driving down test scores. A 2015 study from the National Bureau of Economic Research looked at the effect of heat on student achievement. The authors examined standardized test scores of 8,000 students over nearly two decades across the United States. Then, they determined the average temperature in each child’s county on the day of her test to see how outside temperature impacted performance.

Math scores started to drop off when the temperature outside topped 22º C (71.6º F). While heat had no apparent effect on reading comprehension, the authors noted that “mathematical problem solving utilizes functions of the brain that are distinct from the other subject areas, and different parts of the brain are differentially affected by temperature.”

Theses findings line up with prior studies showing that heat impairs memory, limits attention and slows information processing. In short, more heat means more mental errors.

“There’s a saying that says ‘teachers can make the weather in their classroom’ — but it really is harder when the actual weather is creeping into the room!” said Rebecca Egler, a New York City schoolteacher.

“Hot days are definitely some of the hardest to teach on. When the building is really hot, students are generally (and understandably) more lethargic and often distracted,” said Egler. “Much of this is often due to low, or non-functioning air conditioners, which are often an issue only in schools that serve low-income students.”

Carbon pollution impairs cognitive function.

The pollution driving the rise in temperatures also has a direct impact on human health, and kids are particularly vulnerable.

“My son has asthma, so hot, polluted days make it hard for him to breathe and run around and play — which are the hallmarks of childhood,” said Garofalow. “I hate to see him out of breath, wanting to come inside.”

Scientists have long understood traditional pollutants are bad for brains. Now, they are beginning to understand that atmospheric carbon dioxide — thought by many to be harmless in small doses — can also impair cognition.

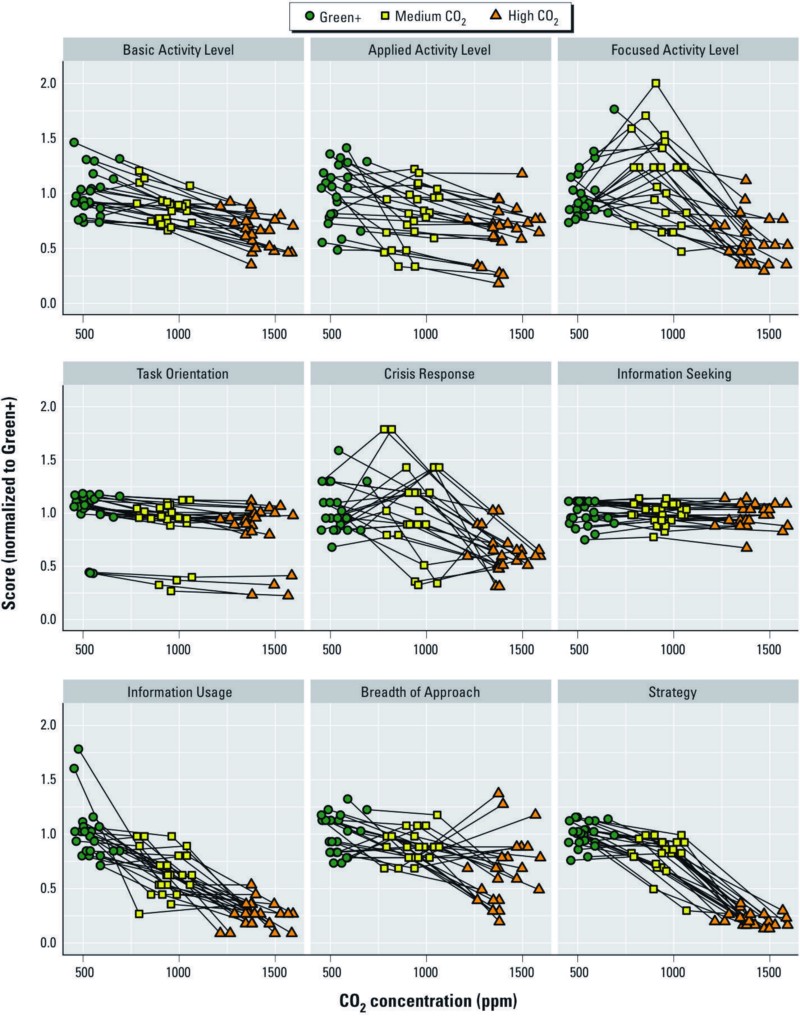

A recent study from the Harvard School of Public Health found that cognitive performance dramatically worsened as indoor concentrations of carbon dioxide rose to 1,000 and 1,500 parts per million. (For a fuller accounting of these effects, see ThinkProgress’s reporting on carbon dioxide and cognition.)

This poses a challenge because carbon dioxide concentrations tend to be higher in cities and much higher indoors, particularly where bodies are crowded and ventilation is poor. A 2012 study on indoor carbon pollution noted that CO2 concentrations in primary school classrooms in California and Texas regularly exceeded 1,000 parts per million ppm and could reach as high as 3,000 ppm. The average atmospheric level of carbon dioxide currently stands at around 400 ppm.

This is a problem we have seen before.

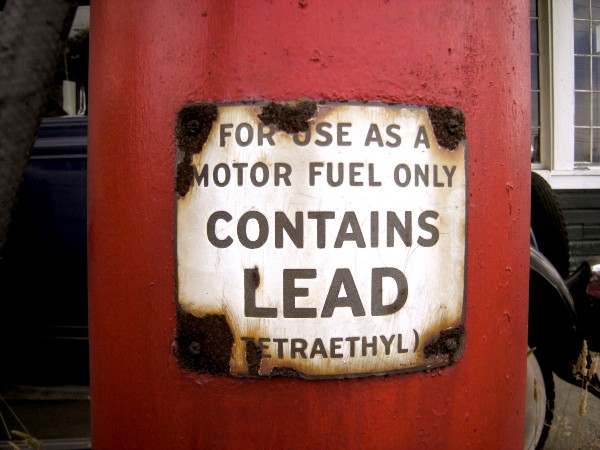

Fossil fuels are often likened to tobacco — dangerous, addictive and sold by powerful moneyed interests. But, in this case, lead may offer a better point of comparison.

For most of the 20th century, gas companies added tetraethyl lead to gasoline to boost octane levels and improve fuel efficiency. Scientists knew long ago that lead posed a threat to human health, but it wasn’t until 1973 that the Environmental Protection Agency began to phase out lead from gasoline. For decades, automakers and oil companies denied findings that lead distorted brains, producing learning disorders and violent or impulsive behavior.

As lead was removed from gasoline and other products, violent crime and teen pregnancy dropped. IQ scores rose. An entire generation was smarter, safer and healthier as a result.

Carbon pollution and severe heat may one day be seen as like the lead of the 21st Century — a pervasive environmental hazard that undermines the cognitive function of children everywhere, making school more challenging and less fruitful. For policymakers, the challenge is similar. How do you phase out a dangerous product that people use every day?

There are ways to cope with heat and indoor carbon pollution, including better ventilation and air conditioning. Garofalow said that air conditioning has made it easier for her daughter to concentrate because, “when she is hot she can only think about being hot, not what the teacher is saying.” As with most carbon quandaries, the best remedy is to cut emissions of the heat-trapping gas.

“My students are bright, hardworking and passionate, and I hate the idea that irreparable environmental damage is going to prevent them from contributing fully to our society,” said Egler. “They have a lot to give us, and we will collectively miss out if they are unable to do so.”

This post has been updated.

Jeremy Deaton writes for Nexus Media, a syndicated newswire covering climate, energy, politics, art and culture. You can follow him at @deaton_jeremy.