Is carbon dioxide racist? Can pollution discriminate? It seems an odd notion since after all — don’t we all breathe the same air?

Members of Black Lives Matter UK made headlines this week by chaining themselves together on the runway of the London City Airport to protest climate change. “Black people are the first to die, not the first to fly, in this racist climate crisis,” they said on Twitter.

Globally, the wealthiest people have the biggest carbon footprints, but it’s the poorest who are most vulnerable to climate change. They often live in the most dangerous places and lack the resources to adapt to rising temperatures and extreme weather. It’s a worldview that more and more people are coming to embrace.

But not if Koch Industries has anything to do with it. They have, unsurprisingly, a contrary argument that fossil fuels are friends of the disadvantaged. The company is funding a reported $10 million-a-year campaign that posits oil, gas, and coal fuels are needed to lift poor people of all colors out of poverty.

The campaign is called Fueling U.S. Forward, and it’s the latest effort to give oil and gas a cultural makeover. At the helm stands Charles Drevna, longtime oil lobbyist and former president of the American Fuel & Petrochemical Manufacturers.

“We’ve got to take this to the emotional and personal level,” said Drevna at the Red State Gathering in August. “Oil and natural gas — they’re not the fuels of the past or maybe the present or a necessary evil. They are the future.”

The thrust of Drevna’s remarks is that our vast wealth is built on cheap fossil fuels, and government efforts to promote clean energy deprive taxpayers and harm oil producers. He wants the world to believe that when production stalls and the price of gasoline spikes, low-income communities and communities of color are hardest hit.

“We’re partnering with other organizations too, especially non-traditional allies like the minority community,” said Drevna. “Who in the heck gets hit hardest and fastest when there’s an energy crisis and prices go up? They do.”

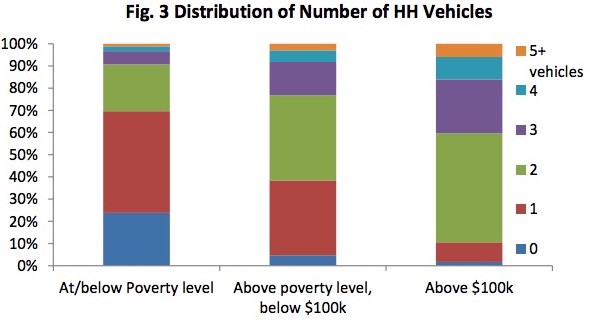

Decrying anything that increases the cost of living has a good chance of getting traction in our age of growing economic inequality and stagnant wages. Most Americans pay more for transportation than they do for food. Low fuel prices mean more discretionary income for working-class families.

“A diverse energy mix — including domestic oil and natural gas — is the key to ensuring Americans continue to grow, innovate, and thrive into tomorrow,” reads the campaign website.

This fossil-fuel-boosting argument claims to be all about the numbers, but what happens when we examine its component parts?

The status quo — should it stay or should it go?

The Fueling U.S. Forward campaign is a love letter the status quo, an effort to rebrand business as usual. The website urges no policy goals or ambitions; it makes no specific recommendations. Drevna offered no call for energy generation innovation in his remarks last month, although he did repeatedly disparage clean energy subsidies.

Fueling U.S. Forward essentially argues for a continuation of the status quo. But how’s that working for families at the bottom of the income distribution so far? For decades, our economy has run on fossil fuels. And yet, millions of Americans struggle to pay their electric bills and put food on the table.

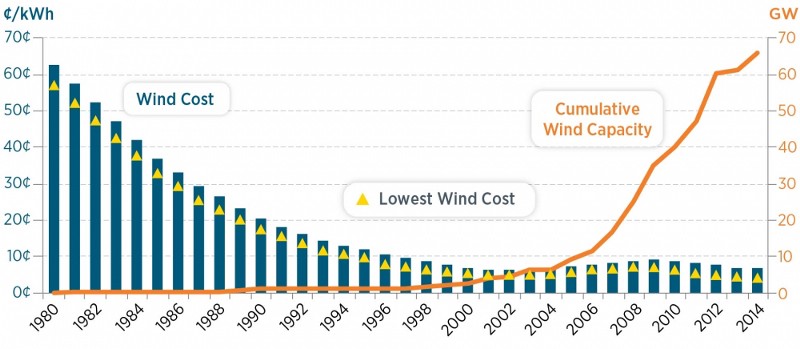

The Koch-inspired campaign claims clean energy would make life worse for working-class families. But despite fears of sky-high costs of wind and solar, the shift to clean energy could actually produce lower electricity bills. According to analysis from Synapse Energy Economics, the Clean Power Plan, the EPA initiative to curb carbon pollution from power plants, would shrink power bills by incentivizing low-cost clean energy and energy efficiency.

The proliferation of electric cars could also benefit low-income families. Increased adoption of Tesla sedans and Chevy Volts will drive down the costs for electric vehicles and suppress the price of gasoline. (Though, for many low-income families, the point is moot. Working class city dwellers get to work and school on public transit. They would be better served by a more robust and affordable public transportation.)

The true cost of fossil fuels

That, however, is not the full picture. Even if oil and gas are cheap on paper, they inflict damage not reflected in their price, what economists and energy wonks call negative externalities.

Every gallon of oil produces pollutants. Heat-trapping greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide fuel planetary warming and, by extension, heat, drought, coastal flooding and high-powered storms. Other pollutants, like carbon monoxide, nitrogen dioxide, and particulate matter have variously been linked to asthma, lung cancer, heart disease and birth defects, among other maladies.

The cost of all this mayhem adds up. According to a 2015 study from Duke University, it comes out to $3.80 per gallon of gasoline burned. Who foots the bill?

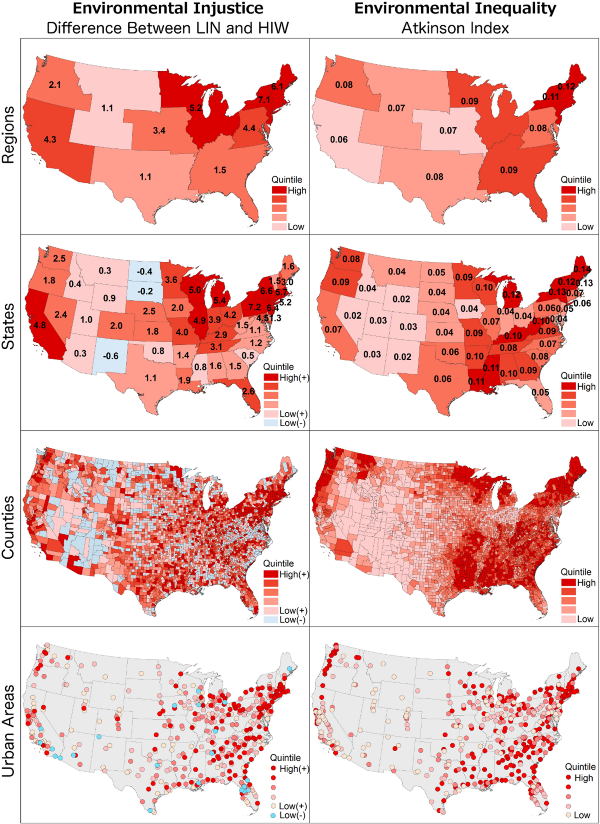

Overwhelmingly, it’s low-income communities and communities of color. On average, in the United States, people of color breathe air with nearly 40 percent more nitrogen dioxide than their white counterparts. They pay for polluted air with degraded health, high mortality, and high hospital bills.

We see the same thing with climate change. When drought hits, farms dry up and the price of food rises, poor families are hit the hardest. When destructive storms strike, it’s low-income communities who stand in the line of fire. Hurricane Katrina produced the most visible example of this injustice — struggling families without the means to escape the storm or rebuild in its aftermath suffered most. According to the World Bank, climate change could edge an additional 100 million people into extreme poverty by 2030.

Drevna’s complaint about clean energy subsidies neglects the built-in subsidy provided for fossil fuels. The costs of climate change and air pollution aren’t paid at the pump. They are paid by taxpayers and vulnerable communities.

The new normal

The Fueling U.S. Forward campaign is presumably the brainchild of some smart people. Which is all the more disappointing for its lack of originality and vision. It claims, despite a preponderance of evidence, dirty fuel is good for everyone, and especially good for people who struggle to pay their bills. This is simply not true.

What’s even more disappointing is the campaign’s lack of vision. Climate change, air pollution, and the disparities from their impacts exist as a product of the status quo. How does “more of the same” produce meaningful change?

Fortunately, improvement is already underway — driven by those who are not funded by fossil fuel interests. Today, wind is the cheapest source of energy in the United States — even without subsidies. Solar is closing in. Falling costs for renewables have spurred skyrocketing demand. Last year, wind and solar made up two-thirds of new generating capacity. The result is cleaner air and rapid job growth in clean energy. There are now more solar workers than coal miners in the United States.

The oft-repeated claim that clean energy threatens low-income Americans is a fallback position in battle over public opinion and increasingly embarrassing for those who cling to it. When concerns about climate change and air pollution mount, fossil fuel producers decry renewables as unreliable and costly, and claim they pose an undue burden on the very poor. Scholars recently dubbed this line of reasoning neoskepticism.

This dying argument willfully ignores an overwhelming trend that points toward zero-carbon energy, towards cleaner air and economic growth. It is a retreat from the promise of innovation and reflects a fear of the future.

You can keep an eye on the Koch front-group, “Fueling U.S. Forward,” at the DeSmog project, “Koch vs. Clean.”

This post has been updated.

Jeremy Deaton writes for Nexus Media, a syndicated newswire covering climate, energy, politics, art and culture. You can follow him at @deaton_jeremy.