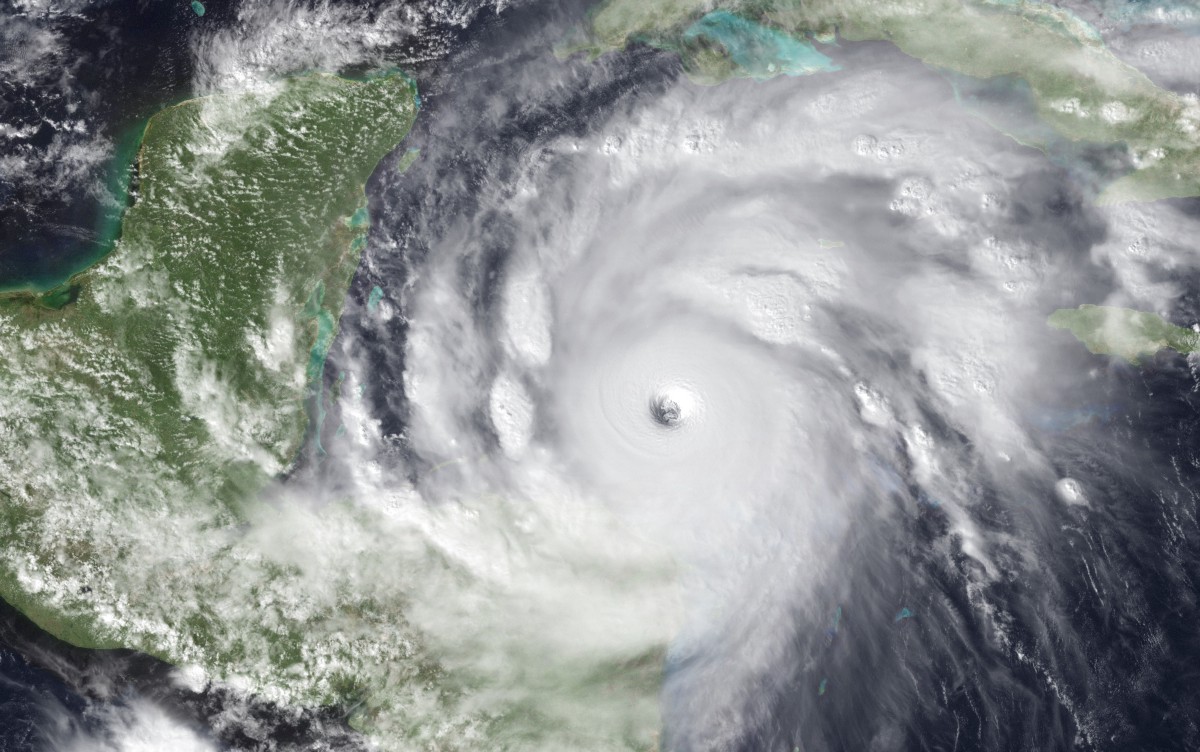

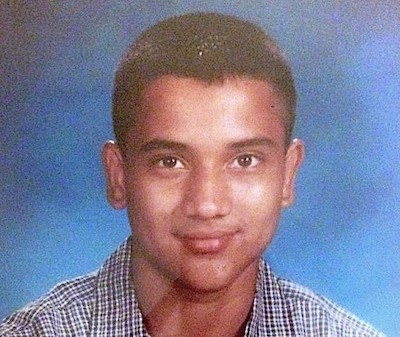

Hurricane Mitch killed more than 11,000 people, but Jose Luis Zelaya was not one of them. Screaming winds snapped trees in two and surging floodwaters swallowed up village after village with lethal indifference, but Zelaya, who was 11 when the storm stuck Honduras, managed to escape with his life. He was rescued after scaling the roof of his shanty to escape the torrent, clinging to his five-year-old sister for fear the current would drag her away.

“The water just kept coming and coming. It was chaotic. It was horrible,” he said. “I remember people dying and seeing their bodies being taken by the river.”

After the storm, food, water and medicine were hard to come by. “You were not even able to go to the neighborhood where you lived because of all the aftermath, all the mud, all the insects, the mosquitoes, the smells, the dead people, the bodies,” he said. “The things that happened afterward were painful, man. That’s why so many people migrated.”

Zelaya’s mother and sister were among the migrants who fled to the United States to escape the turmoil in Honduras. He said that he does not resent his mother for leaving him behind. “For me, that was the right thing to do. Save her,” he said, adding that he could take care of himself, that he could provide for the family, and that, some day, he hoped to join her.

This is a story of migration in the age of climate change. It is as much a record of history as it is a harrowing glimpse into an increasingly perilous future. Hurricanes are fueled by heat. 1998, the year that Mitch devastated Central America, was the hottest year ever recorded, a record that stood until 2005, the year that Hurricane Katrina struck. This was later eclipsed by 2010, a year so hot that it is only surpassed in the record books by 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017 and 2018.

Every lump of coal or gallon of gas burned is propelling humanity into a new and dangerous era in which the once predictable balance of warm and cool, wet and dry, will give way to punishing heat, lasting drought and ferocious storms. The same forces that fueled Hurricane Mitch are now depriving farmers in Central America of desperately needed rainfall, sparking a new wave of immigration. This is just a preview of things to come. By one account, rising seas alone could displace as many as one in five people by the end of the century.

To prepare for the coming century of mass migration, Americans need to learn how immigration works today. A look at the last 50 years of migration from Latin America can can help us grapple with the forces that drive people to leave the only home they have ever known, and it can help us understand how immigration policy shapes their journeys to the United States.

For two years after Hurricane Mitch, Zelaya continued to live with his physically abusive father in a community that was mired in gang violence. It was hard to stay but harder to go, and it was not until he was nearly killed playing soccer that he resolved to leave the country. One day, while he was kicking a ball around with this friends, a pair of stray bullets punctured his arms, the collateral damage of a drive-by shooting. He was 13. It was then that he decided finally to try to reunite with his mother and sister.

Zelaya’s mother hired coyotes, men paid to smuggle immigrants into the United States, to bring him from Honduras. It took him 45 days to make the trek, a journey of more than a thousand miles that culminated in his swimming across the Rio Grande. Once he arrived, authorities picked him up and detained him for another two months.

He recalls crying and crying, wondering if he would ever see his mother again. When they were finally reunited, he said, it was the most beautiful moment. “Not knowing whether I was going to be sent back to Honduras, or whether I was going to die on the journey, or whether I was going to die at home, I somehow made it to her,” he said. “I was thankful to life and to God and to her and to everybody that made it possible.”

Zelaya’s story highlights the difficulty of reaching the United States and the barriers that face immigrants once they arrive. It wasn’t always this way. Recent decades have seen a major shift in immigration policy — and in the way we think about immigrants — that made Zelaya’s journey that much more treacherous.

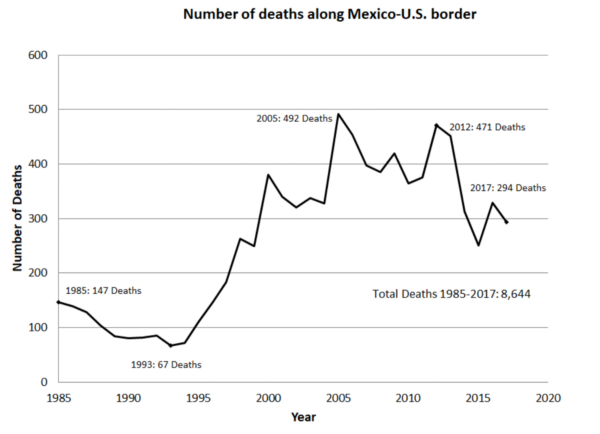

The militarization of the border has also led to thousands of deaths — and an uptick in the number of undocumented immigrants.

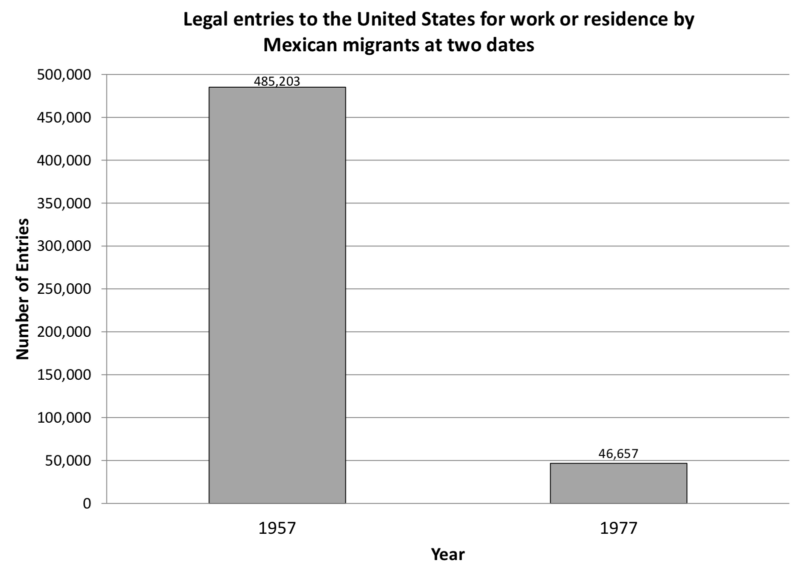

In 1965, Congress set out to reform America’s racist immigration system, which barred immigration from Asia and the Middle East, even while it set no limit on immigration from Mexico. In the spirit of equity, lawmakers updated the statute to issue the same number of visas to immigrants from every country, thereby imposing a limit on Mexican immigration where none had previously existed. Lawmakers also ended the guest worker program with Mexico, which they viewed as an exploitative labor scheme akin to black sharecropping in the South.

Though well-intentioned, these reforms had the effect of criminalizing the regular flow of migrant labor from Mexico. “The conditions of labor supply and demand hadn’t changed,” said Douglas Massey, co-director of the Mexican Migration Project at Princeton University. “Millions of Mexican workers had established connections with employers in the United States and communities in the United States, and so the flow [of labor] pretty quickly resumed under undocumented auspices.”

The change in policy precipitated a dramatic change in views of migrants. “Now, they were all illegal migrants, and so they could be framed as criminals and lawbreakers and a threat to the country,” Massey said. “That really contributed to the ongoing trope in the American media of this threat of immigrants from the south who were ‘wetbacks’ and ‘illegals’ and ‘criminals.’”

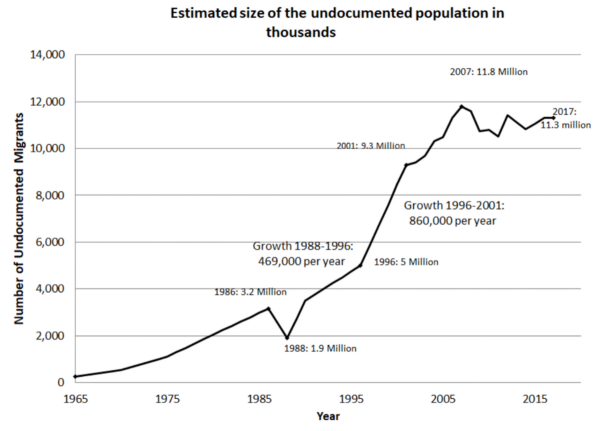

In the years the followed, the border became increasingly militarized. The number of border patrol officers increased more than tenfold, from around 1,600 in 1971 to some 19,000 today, as elected officials pushed for greater enforcement. This shift had two notable consequences, neither of which was to meaningfully slow the influx of Mexican immigrants.

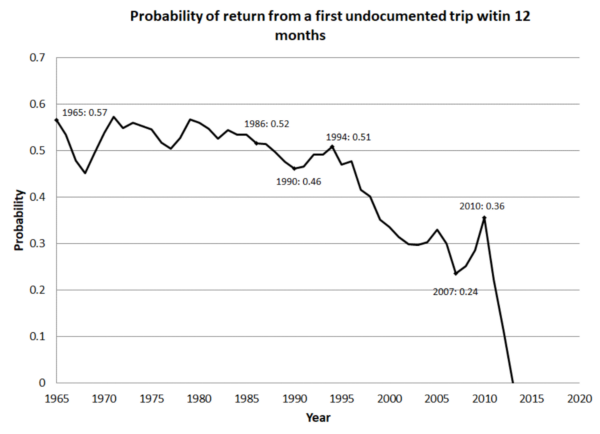

First, the militarization of the border discouraged migrant workers from returning home to Mexico by making it riskier for them to come back to the United States. “From 1965 to 1985, most of the movement was really highly circular,” Massey said. “Most of the Mexicans who were migrating in the 80s and 90s did not want to settle here, and they were circulating back and forth reasonably well until we made it impossible and very dangerous and expensive to go back and forth on a regular basis.” Rather than return home, millions of undocumented migrants settled permanently in the United States.

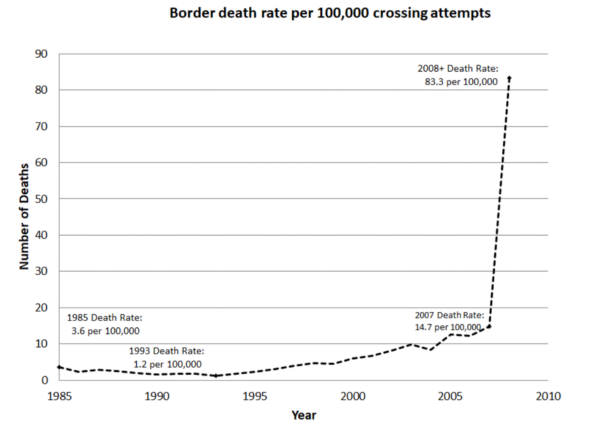

Tougher enforcement also took an immense human toll. Immigrants who had once traveled through border cities like San Diego, California and El Paso, Texas began to avoid these points of entry, which were heavily policed. Instead, they crossed through unforgiving landscapes like the Sonoran Desert and the Lower Rio Grande Valley, where many died because they lacked water, food or medical care.

Between 1985 and 2017, authorities found the remains of 8,644 migrants along the border with Mexico. Because bodies quickly decay in the desert, many of those who perished were likely never discovered, meaning the actual number is almost certainly higher. To aid migrants on their journey to the United States, volunteers have placed food and water at locations in the desert, though border patrol officers have been found sabotaging these supplies.

After 2000, Mexican immigration slowed, not as a result of greater enforcement, but as a result of Mexico’s aging population. Migrants tend to be in their late teens and twenties and as the average age in Mexico ticked up, the number of migrants of declined. Today, more Mexicans are leaving than coming. Any promise of greater border enforcement as a means of stemming Mexican migration would ultimately result in wasted dollars.

“You can’t stop a flow that’s already negative,” Massey said. “The U.S.-Mexico border is already the most militarized border anywhere in the world, with the exception of the Korean DMZ, and there’s no traffic along the border except for humanitarian migrants [who are largely coming from Central America] arriving to turn themselves in and ask for asylum.”

While border enforcement has not curbed immigration, it has proved to be an imminently useful tool for politicians, Republicans in particular. The militarization of the border has allowed politicians to portray America’s southern border, a peaceful boundary between two major trading partners, as a battlefront in an ongoing war against an invading horde, one that threatens to steal jobs, filch welfare checks, rape, maim, kill, and otherwise despoil American culture.

“Mexican immigration has become the lightning rod — and Mexican immigrants the scapegoat — for all that is fearful and threatening in the world today,” Massey said. “No matter what the threat was, the all-purpose answer was more border enforcement.”

Numerous studies have found that it was a lurking fear of outsiders — Latin American immigrants, specifically — that led so many voters to favor Donald Trump. That fear was most pronounced in overwhelmingly white cities and towns. Trump found he could win the support of voters in these places by promising to stop the flow of immigrants. “[Xenophobia] works as a great mobilizer for the Republican base,” Massey said. “And right now that base has been reduced pretty much to older white people who are very nativist and anti-immigrant and a little racist.”

The push for greater border enforcement is entirely symbolic and unlikely to achieve the intended effect. “Our immigration and border policies, with respect to Mexico, may have served the political purpose of diverting attention away from other pressing issues and giving citizens a concrete focus for their fears and insecurities, but they have completely backfired in their efforts to reduce migration to the United States,” Massey said.

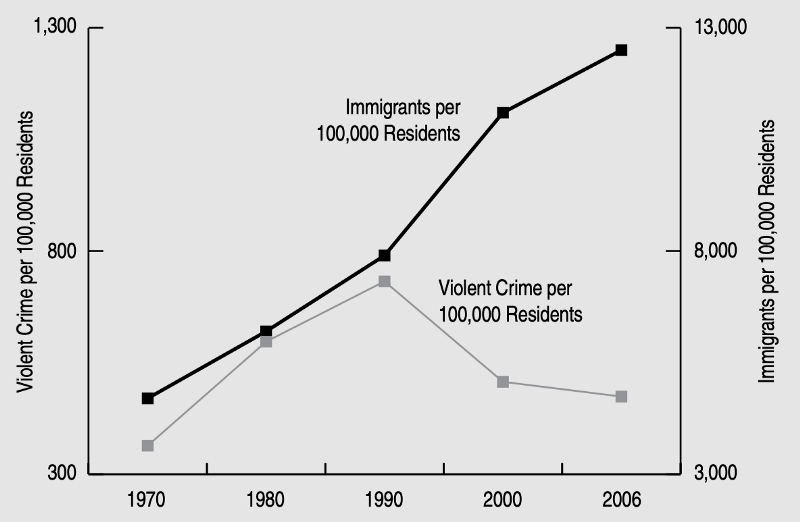

Immigrant communities drive down crime by helping newcomers find work and housing.

Much of the xenophobic hysteria gripping the Republican party is driven by a fear that immigrant enclaves will be a source of crime. The fact is, immigrant communities help reduce violent crime by helping newcomers find work and housing, and by incentivizing them to stay out of trouble.

Nadia Flores-Yeffal, a sociologist at Texas Tech University and author of Migrant-Trust Networks, has cataloged the ways that immigrants already living in the United States help others gain a foothold in the United States. “When two people are from the same place of origin, they come and they identify with each other,” said Flores-Yeffal. “They house them in their home for a long time, until they get a job. They feed them. They buy them clothes.”

She should know. Flores-Yeffal is herself a Mexican immigrant. When she was just 16, she followed her husband across the border in search of work. At that time, jobs were hard to find in Mexico and inflation was high. “I would go to the store every day to buy meat, and I would get fewer grams of meat every day for the same amount of money,” she said. She and her husband, who were both undocumented, moved to a community with immigrants from rural Mexico living near Los Angeles. Their new neighbors helped her husband find a job, took Flores-Yeffal to English classes and looked after their newborn daughter.

With the help of the immigrant community, what she has since termed a “migrant-trust network,” Flores-Yeffal found her way in the United States. She started taking classes at a community college and later transferred to the University of California Irvine, where she began her research on migration-trust networks. Eventually, she made her way to the University of Pennsylvania, where she earned a PhD under the supervision of Douglas Massey — while raising five children. It is a feat she could not have achieved without the help of her community.

Flores-Yeffal said that migrant-trust networks include not just migrants, but also employers and landlords willing to work with undocumented immigrants. Each member extends trust and assistance, often without the formal protection of the law. Flores-Yeffal said that such strong community bonds have numerous benefits. Workers are incentivized to work harder, for example, because their work will reflect on the friend or family member who helped them find a job, and they are less likely to resort to crime because they are able to find work. Also, they know that if they get in trouble, they put the entire community of undocumented immigrants at risk.

Mexican immigrants tend to belong to strong migrant-trust networks, which helps suppress crime. Harvard sociologist Robert Sampson has found that there is actually a lower rate of violence among Mexican-Americans than among other groups. “A major reason is that more than a quarter of all those of Mexican descent were born abroad and more than half lived in neighborhoods where the majority of residents were also Mexican,” he wrote in The New York Times. “Our study further showed that living in a neighborhood of concentrated immigration is directly associated with lower violence.” He has suggested that the rising number of undocumented Mexican immigrants in the 1990s contributed to the dramatic drop in the overall crime rate.

Sampson’s research highlights the vital role of immigrant communities, and the need to make jobs and schooling available to newcomers. When immigrants can’t tap into existing communities and find work or get an education, the results can be disastrous. Consider the fate of many Salvadoran immigrants.

In the 1980s, a brutal civil war in El Salvador spurred a wave of immigration to Southern California, where there was no preexisting Salvadoran community. “The social networks of Salvadorans… were very weak, very fragmented, unlike those of Mexicans,” Massey said. Young, undocumented Salvadoran men soon found themselves on the streets of Los Angeles unable to find work or attend school, so they formed gangs, the most famous of which is Mara Salvatrucha, better known as MS-13.

Under the leadership of Ernesto Deras, a Salvadoran veteran who had been trained by U.S. military advisors, MS-13 became a powerful criminal force, extending its presence to Central America. Members of MS-13 who were arrested and deported back to El Salvador continued their operations there. Today, gang violence is a chief driver of migration from El Salvador to the United States.

“What we have now are families and children arriving at the southern border, and they’re crossing the border in order to get caught,” Massey said. “They want to apply for asylum or refuge, and then they’re treated like criminals and incarcerated and separated.”

Immigration is inevitable, so the United States should make it easier for immigrants to enter and assimilate.

In speaking about immigration, Flores-Yeffal outlined the powerful forces that compel people to migrate, what she called pull and push factors. People are pulled to migrate by the promise of higher-paying jobs in a new country. “If you have a demand for labor, it is going to be satisfied by a supply, and it’s not going to matter what you do with the border,” she said. Separately, people are pushed when a natural disaster or the threat of violence has made it unsafe to stay put. Climate change promises to push more people to the United States. “It’s not going to matter if you have a fence,” Flores-Yeffal said. “People are going to find their way.”

By 2080, declining crop yields in Mexico could send over 6 million more people to the U.S. border, which is to say nothing of migrants from the multitude of countries threatened by storms, droughts and rising seas. The response to the coming wave of mass migration could be one of compassion. Wealthy nations, better insulated against the ravages of the climate crisis, could open their doors to climate refugees. But leaders in Europe and the United States could also respond with more nationalism and isolationism, border walls and travel bans. The latter scenario is entirely plausible, if not probable.

The nativistic spasm that sent Donald Trump did not come in response to a real crisis. At the time of his election, the number of undocumented immigrants living in the United States was at a ten-year low. In his time in office, Trump has focused on deterring new migrants with draconian family separation policies. Currently, as a surge of thousands of Central American asylum seekers each month strains Customs and Border Protection, he is threatening to close the border with Mexico rather than expand processing facilities to accommodate the influx of families escaping violence and destitution.

What happens when crop failures and resource wars abroad spur not thousands, but millions to seek refuge in the United States?

The United States and other wealthy countries bear much of the blame for planetary warming, while many of the countries at greatest risk of climate change — warm, coastal nations like Somalia and Bangladesh — have contributed least to the problem. For that reason, if no other, advocates have said the United States has a duty to welcome climate refugees.

In practical terms, that means decriminalizing undocumented entry into the United States and making it easier to gain entry and earn a work permit. It means incentivizing employers to offer English-language training to employees and making it easier for skilled workers — doctors, lawyers, engineers — to become credentialed in the United States. It means finding a way to grant asylum to people who don’t have a way to show they were victims of climate change. Most importantly, it means thwarting the forces of fear and anger that have relegated so many immigrants to the shadows.

Currently, the United States is pursuing an immigration policy that makes it dangerous — even deadly — to enter the country and challenging to assimilate, a policy that ultimately discourages immigrants from returning home. The government is sending refugees to prisons where children are torn from their parents’ arms and arresting undocumented immigrants with no criminal record rather than offering asylum to victims of violence and a path to citizenship for the nearly 11 million undocumented immigrants currently living in the United States.

That could change. Jose Luis Zelaya, the Honduran immigrant described at the beginning of this story, is optimistic about the possibility of comprehensive immigration reform. “I think that as a nation we are ready to do what’s right and to do what’s moral,” he said. He believes that stories like his can help Americans understand why people come to the United States and how they can contribute to this country.

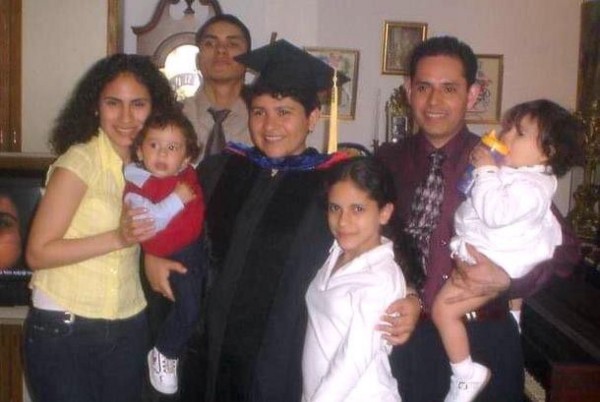

With the help of his family and his church, Zelaya managed to make his way through school and is currently earning his PhD at Texas A&M University, where he studies urban education, focusing on students who are learning English as a second language. “I am extremely grateful to the United States for all the contributions and opportunities it has given me,” he said.

Zelaya said that he wants to help immigrant students in the United States. He wants to work in Honduras, where he hopes “to build schools and work with different communities to find solutions to some of these problems that I experienced and that people continue to experience today.” In a world beset by rising temperatures and deepening nativism, he remains uncommonly hopeful about the future and his place in it.

“It’s been a crazy journey, man. I’m about to be a doctor,” he said. “I’m ready to be Dr. Zelaya. I’m ready to work. I’m ready to get involved, and I’m ready to get my hands dirty.”

Jeremy Deaton writes for Nexus Media, a syndicated newswire covering climate, energy, policy, art and culture. You can follow him @deaton_jeremy.