In the Lake Apopka region of Florida, a typical August day might yield a high temperature of 92 degrees F, a heat made all the worse by the stifling humidity. The weather is bad enough for office workers who spend most of the day next to an air conditioner. For farm workers, who spend their August picking blueberries outdoors, the heat can be oppressive, even fatal.

Heat can induce dehydration, nausea, exhaustion, stroke and death. Even among workers who endure little discomfort, heat can take a toll over time. Chronic dehydration, for example, can lead to kidney failure. Despite these risks, there is no federal standard protecting workers from extreme heat.

“Hotter temperatures beget fewer full work days, exhaustion and fatigue,” said Jeannie Economos, the pesticide safety and environmental health project coordinator for the Farmworker Association of Florida. “It’s even worse when you have to pick fast because farm workers are paid by the piece, not the hour. This is a big deal when you’re trying to bring home wages that can support a family or pay a car bill — plus these folks don’t have health insurance.”

Economos led a group of experts, advocates and reporters around a farm near Lake Apopka Sunday to explain the risks of extreme heat. The outing was part of the newly launched Freedom to Breathe Tour. Organized by environmental leaders from across the South, the tour will highlight the dangers of climate change for people living on the margins, including farm workers, who are struggling with rising temperatures.

“We’re finding more and more people that have dehydration. They have symptoms of heat stress, so they’re really concerned about that. Plus, workers are afraid to report their symptoms,” Economos said. “Their afraid to report to their supervisor or the crew leader or the labor contractor if they have symptoms of heat stress because they’re afraid they’ll be pulled off the job.” Undocumented migrant farm workers are especially vulnerable, as they are less likely to demand rest, shade or water for fear of retaliation.

Earlier this summer, Public Citizen, the United Farm Workers Foundation and Farmworker Justice submitted a petition to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) calling for heat protections for workers. The petition outlines several measures, which would compel employers to provide additional mandatory breaks on hot days, protective equipment such as cooling vests, access to water and shade, and additional training and monitoring of workers.

“They often can’t take breaks to drink water. And even if they do drink water, they don’t want to, because that makes them need to go to the bathroom more often, and they don’t want to stop,” Economos sad. When you’re being paid by the piece, she added, “you don’t want to stop work to go to the bathroom, because that means that you’ll have a lower production.”

Farm work is so demanding and laborers are in so much discomfort, that it is often difficult to identify heat stress. “A lot of the symptoms of pesticide exposure and heat stress are the same, so a lot of the farm workers won’t know. Or they can be the same symptoms of having the flu,” Economos said. “Farm workers are working around the clock and throughout the year in conditions that most of us would not accept.”

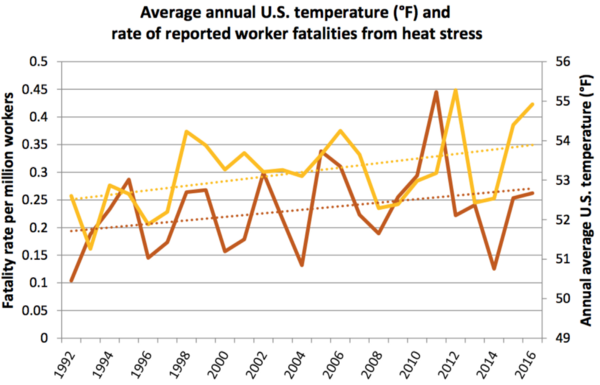

It’s not just farm workers that are suffering in the heat. Between 1992 and 2016, nearly 800 workers died in extreme heat, while close to 70,000 suffered serious injury, according to data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. As bad as those numbers sound, they likely obscure the truth. OSHA said that heat-related “deaths are most likely underreported, and therefore the true mortality rate is likely higher,” though it also concluded that heat deaths are too rare to justify new standards. Advocates warn that rising temperatures will make outdoor work more dangerous and heat-related deaths more commonplace. The time to implement strong federal standards, they say, is now.

“There is an undiagnosed epidemic of heat-related illness and death in this country, and the problem will get much worse very quickly because of global warming,” said David Arkush, managing director of Public Citizen’s climate program. “Some of our most vulnerable workers are at the highest risk. We need to protect them right away, and we need aggressive action to halt greenhouse gas pollution and stop climate change.”

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, a federal agency that investigates workplace hazards and makes policy recommendations, has urged OSHA to adopt a heat standard for decades. While California, Minnesota and Washington all have heat protections for workers, as does the Pentagon, there is no federal standard guarding civilian laborers. OSHA has said that heat is covered by the “general duty” clause of Occupational Safety and Health Act, which mandates workplaces be “free from recognized hazards.” But OSHA has done little to guard workers from high temperatures, issuing just 28 heat-related citations on average each year from 2013 to 2017.

“A few years ago, OSHA came out with recommendations for heat stress, which included rest, shade and water. And the recommendations are great. Workers in outdoor environments need rest, shade and water,” Economos said. “But they’re only recommendations. If there is not a regulation that mandates that employers give rest, shade and water to their workers, it’s not going to happen.”

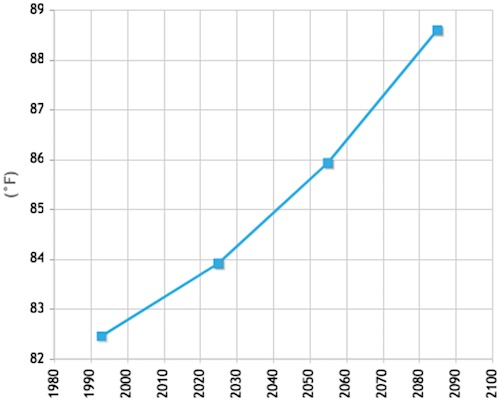

Scorching temperatures aren’t just a threat to health and safety. Workers also accomplish less when toiling under a hot sun. Researchers quantified the loss in productivity in a 2010 study of Caribbean countries, finding that productivity starts to drop off little by little once the mercury tops 78 degrees. The average annual high in Florida is more than 83 degrees F. By mid-century, it’s expected to hit 86 degrees, and it gets worse from there. Productivity lost to heat adds up day after day, year after year. The global economy could lose up to $2 trillion by 2030 as rising temperatures make it difficult to work outdoors, according to a 2016 study. Tropical regions are set to take the biggest hit.

All of this will mean more physical stress and financial hardship for America’s farm workers. “Farm workers do some of the most important work in the entire country,” Economos said. “They feed the rest of us. We would not be here right now if we had to sit and worry about where our food came from every day.”

Jeremy Deaton writes for Nexus Media, a syndicated newswire covering climate, energy, policy, art and culture. You can follow him @deaton_jeremy. Josh Landis contributed to this report.