You might know the feeling — after months of encouraging news from your bathroom scale, you discover the device is broken. The outlook on your weight-loss goal is worse than you realized.

Scientists just went through something similar, except instead of a scale, it was a system of satellites, and instead of your winter weight, it was the Greenland ice sheet.

Researchers have been tracking the melting of the Greenland ice sheet by satellite. It now seems there was an error in measurement. A new study published in the journal Science Advances finds the ice is melting 7 percent faster than previously thought.

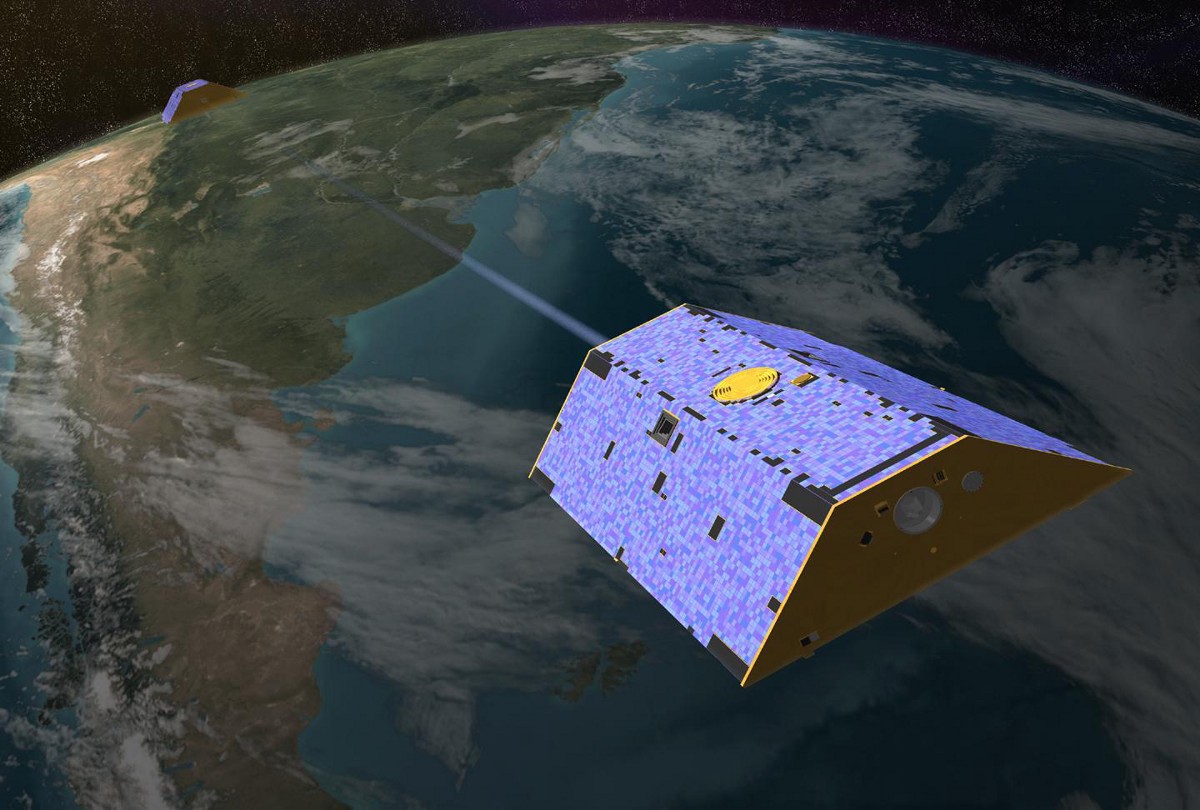

Scientists use satellites to map Earth’s gravity field, gathering information about the distribution of mass around the globe. Earth doesn’t exert gravity equally in all directions. Where there is more mass, satellites detect a stronger gravitational pull.

Using satellite data, scientists can measure the melt of Greenland’s ice sheet. As ice dissolves, the island loses mass and exerts a weaker gravitational pull — at least that’s the idea.

In practice, it’s a little more complicated. Satellites can only detect a change in mass. They can’t determine how much of that mass is ice, how much is land and how much is mantle ebbing and flowing beneath the earths’ crust.

“[The system] cannot tell the difference between ice mass and rock mass,” said study co-author Michael Bevis, professor of earth sciences at Ohio State. “So, inferring the ice mass change from the total mass change requires a model of all the mass flows within the earth.”

Here’s where this gets interesting.

The tectonic plate under North America — including Greenland — has been traveling northwest for millions of years. Around 40 million years ago, Greenland slid over an extra hot column of partially molten rock. This hot spot softened up the crust below Greenland’s east coast. (The hot spot now rests beneath Iceland, where it is driving all manner of volcanic activity — warming hot springs and fueling the country’s geothermal power plants.)

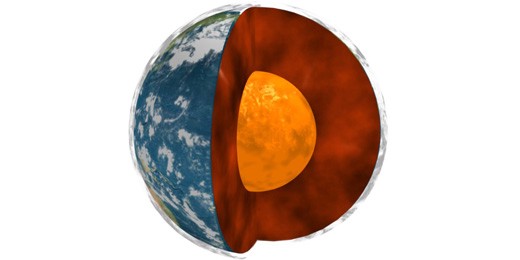

The softening of Earth’s crust beneath Greenland had consequences during the last ice age, when Greenland’s ice sheet was significantly thicker. The weight of all that ice caused the island to sink into the supple crust below. When the ice age passed and the ice began to melt, the island rebounded. Mantle flowed in beneath Greenland, causing the land to rise again. It’s still rising today.

You can imagine how this would interfere with satellite readings. The loss of ice is weakening Greenland’s gravitational pull. At the same time, the accumulation of mantle is strengthening its gravitational pull.

Scientists previously accounted for the flow of mantle, but they underestimated its effect. The study’s authors gauge the flow of mantle by using GPS technology to measure the rise of land at various points along Greenland’s east coast. They discovered that mantle is gathering beneath Greenland more quickly than they had realized.

What this means is that scientists have been underestimating ice loss by 20 billion metric tons per year. And more of the melting is occurring along Greenland’s east coast than previously thought.

“By refining the spatial pattern of mass loss in the world’s second largest — and most unstable — ice sheet, and learning how that pattern has evolved, we are steadily increasing our understanding of ice-loss processes, which will lead to better-informed projections of sea-level rise,” said Bevis.

The study has implications for Antarctica — the 800-pound gorilla of global sea-level rise. Scientist will need to deploy more GPS measurement stations at Earth’s southern pole to accurately measure the flow of mantle beneath the continent and get a better reading of Antarctic ice melt.

Better data will allow scientists to predict future sea-level rise more accurately. That could prove crucial for coastal cities preparing for the impacts of climate change.

Jeremy Deaton writes for Nexus Media, a syndicated newswire covering climate, energy, politics, art and culture. You can follow him at @deaton_jeremy.