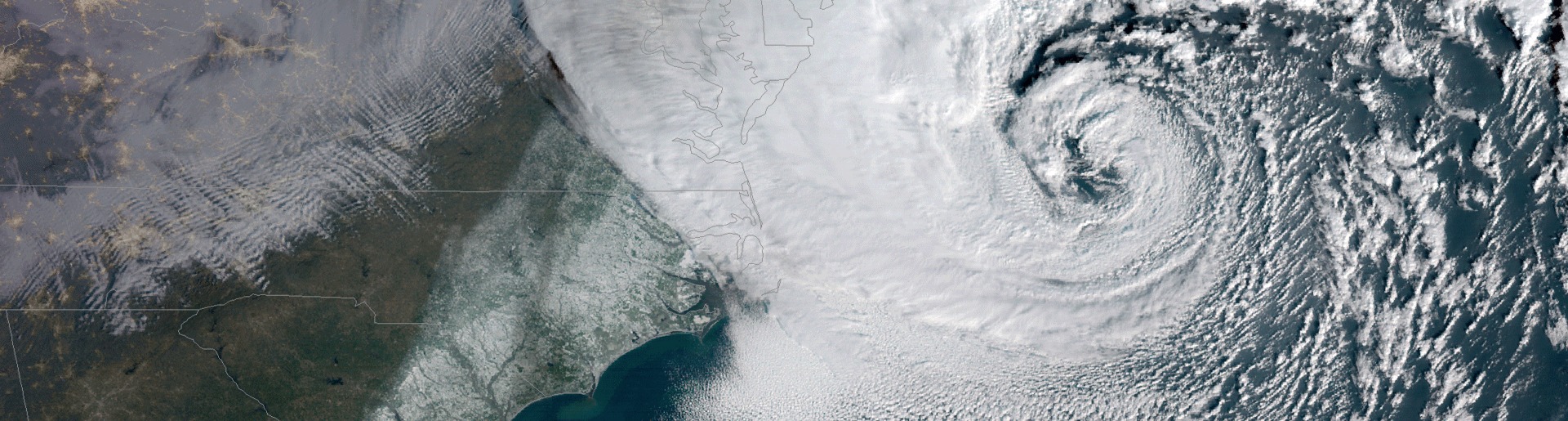

This week a powerful winter storm covered the East Coast in a thick layer of snow. It also delivered frigid temperatures, record tides fueling monster floods, and winds close to 80 mph, leading several governors to declare states of emergency. The dangerous snowstorm is what’s known as a “bomb cyclone.” It’s what happens when cold terrestrial winds collide with warm ocean breezes. The resulting drop in pressure produces what looks like a cold-weather hurricane. So far, at least six people have died as a result of the storm.

Bomb cyclones aren’t new, and, for the most part, they aren’t as scary as they sound. Despite their explosive speed, they typically don’t pack the same punch as a late-summer tropical storm. This week’s tempest is a far cry from hurricanes Harvey or Maria, for example. For that reason, some have objected to the use of the term bomb cyclone — what Ashwin Rodrigues of Motherboard called “the latest in the fear mongerization of winter weather.”

So, is the term bomb cyclone just cold-weather clickbait, or is a little color actually useful in talking about extreme weather? All evidence points to the latter.

There are a couple of things to point out. The first is that “bomb cyclone” is a scientific term used by scientific people to describe scientific things. As such, it is fair game for journalists. That the moniker is also clear, vivid and succinct is a bonus for weather reporters who spend much of their day disentangling terms like “atmospheric blocking” and “thermohaline circulation.”

The second thing to point out is that colorful descriptors like bomb cyclone may actually be helpful in a weather emergency. McGill University climate scientist John R. Gyakum coined the term, in part, he told the Washington Post, “to help raise awareness that damaging ocean storms don’t just happen during the summer.” A little dramatic flair might motivate people to make the necessary preparations in the face of a dangerous, potentially life-threatening winter storm.

Generally speaking, Americans don’t take storms seriously enough. This is partly the product of optimism bias, our tendency to believe that everything will work out for us, even if it doesn’t for everybody else. But it’s also the result of people simply failing to understand the risks. A 2012 study found that U.S. coastal residents tended to downplay the threat of severe flooding and sustained high-speed winds from hurricanes Isaac and Sandy. Because people didn’t understand the risks, authors note, they failed to prepare adequately.

Complicating matters is the fact that public understanding of extreme weather is so easily undermined. Research shows, for example, that people tend to misinterpret the cone of uncertainty, an oft-used graphic showing the likely path of a hurricane. As one study noted, “those outside of the cone tend to feel a false sense of security,” even though they may end up in the storm’s path.

Perhaps the most pernicious example of Americans subconsciously underestimating the potential dangers of extreme weather comes from a 2014 study showing that hurricanes with female names kill more people than hurricanes with male names. While the results of the study have been disputed, they are consistent with the larger trend of Americans being too blasé about severe storms.

“In judging the intensity of a storm, people appear to be applying their beliefs about how men and women behave,” said study coauthor and University of Illinois marketing professor Sharon Shavitt. “This makes a female-named hurricane, especially one with a very feminine name such as Belle or Cindy, seem gentler and less violent.” Because people may underestimate the threat of female-named hurricanes, the study noted, they don’t take the necessary precautions.

If the goal of weather reporting is to help the public understand and prepare for extreme weather, then there is most certainly cause for clickbait. Giving a storm a catchy name like Snowpocalypse or Snowmageddon may do more to alert people than giving it a name Sandy or Katrina. Likewise, terms like polar vortex and bomb cyclone do more to warn people than sober explanations of barometric pressure and humidity.

“The name [bomb cyclone] isn’t an exaggeration — these storms develop explosively and quickly. They can produce destructive winds, coastal flooding and erosion, and, of course, very heavy precipitation,” Gyakum told the Post. “If the term conveys the importance and the danger associated with them, then I think that’s a good thing.”

Jeremy Deaton writes for Nexus Media, a syndicated newswire covering climate, energy, policy, art and culture. You can follow him @deaton_jeremy.