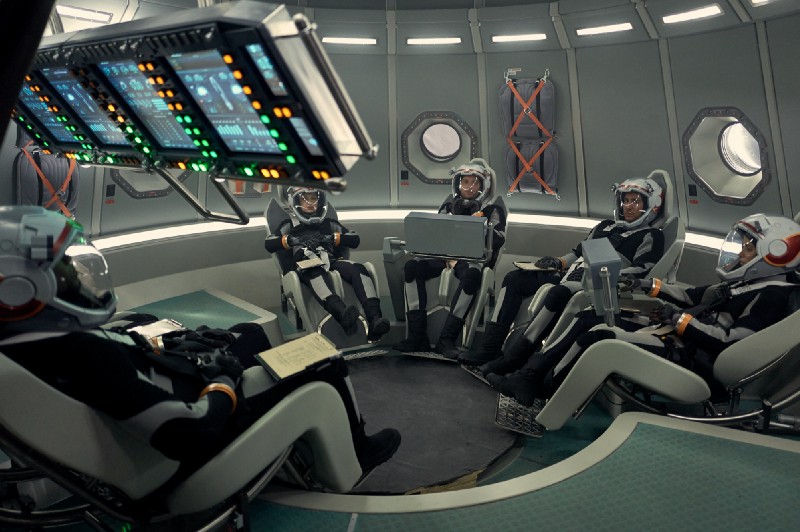

Recently, National Geographic Channel launched Ron Howard’s MARS series, fusing documentary with sci-fi to show how humanity may soon arrive on the Red Planet. Renowned space writer Leonard David wrote the companion book, Mars: Our Future on the Red Planet, interviewing many of scientists and engineers behind the TV program and imagining what it will take to get off this world. David talked with Nexus Media about what we can learn about our planet and ourselves from efforts to explore the solar system.

What can we learn about maintaining our own planet from efforts to study and colonize another one?

That’s one of the themes I made sure was in the book, the ethics question of changing Mars to suit us — making Earth 2.0.

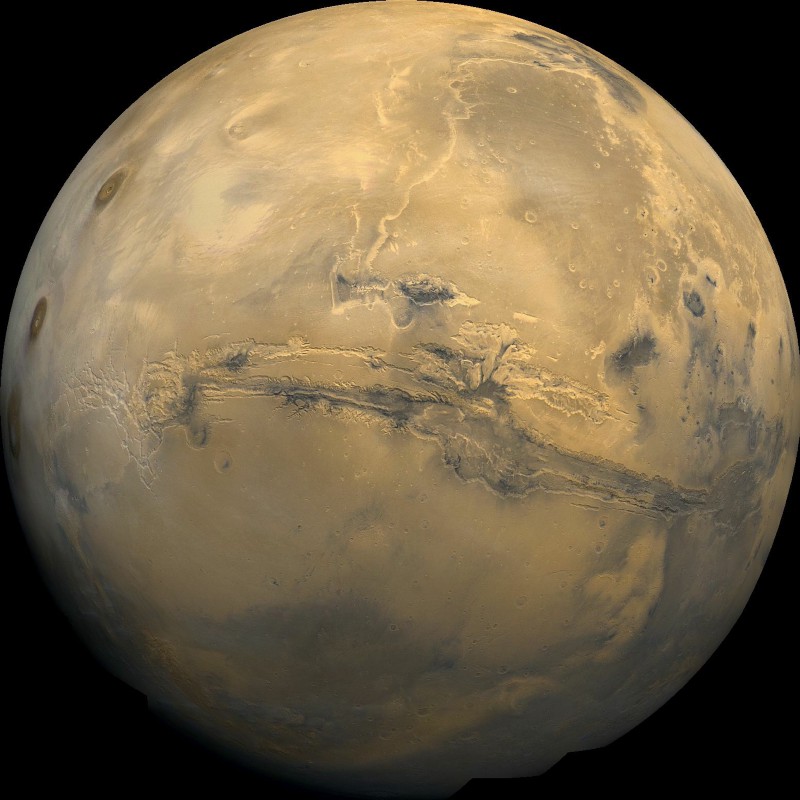

It’s all debatable and under discussion. You have planetary protection people concerned about putting rovers where life might be. How much does it cost to sterilize everything and make sure we don’t contaminate those features? Then you get to the big, big broad picture of, okay, let’s start fooling with the thermostat on Mars, and changing it. We terraform down here on our planet a lot. Agriculture is terraforming, global climate change is terraforming, but not to our liking. Are we learning things that might be ideas and concepts that we haul to another planet?

The life question is haunting in a lot of ways. If life has glommed on to that world and evolved over billions of years, what right do we have to put a foot on it and say, “Well we’re here and we’re going to transform everything to suit us.” We need more information, and I hope readers, when they finish my book, realize that this is something looming large in all the discussions about Mars.

There are some that hastily say: “Well, who cares, we’re there first, never mind them.” But it’s definitely an issue I’m concerned about personally, as much as I want humans to get on the planet.

In science fiction, so much of Mars colonization is the struggle to survive in a desolate world, a trend that goes back at least as far as Ray Bradbury’s Martian Chronicles. But you talk about thriving on the Red Planet, not just survival — what does a future on Mars look like?

It’s still a challenge. You can write around the danger and minimize it, but the planet Mars is always out to kill you — it has a lot of exotic properties that you’re going to have to surmount.

It’s interesting that you mention Martian Chronicles. One of my great experiences meeting another writer was meeting Ray Bradbury. I told him, “I really admire your writing — what’s a success pointer you can give me? How do you write?” And he said, “Look for the metaphor. Look for the metaphor!” When I got done with my book, I asked myself, “What have I learned here?” And I learned a lot. There were times when I was writing the book when Mars seemed almost too dangerous, too exotic a place. But then someone would send me another research paper on something that seemed to be a problem workaround — so I tried to say this is not easy, we’ve got a lot of work ahead, lots of challenges, but Mars is a metaphor. Mars is a metaphor for exploration, for scientific discovery — but also for danger, as well as destiny.

The sci-fi part of this project is the docudrama that’s coming with the National Geographic TV series. That first show is Nov. 14. They cast a fictional crew going to Mars and what they encounter, but the documentary side includes interviews with individuals that are making the reach for Mars real. Some of those same people are featured in my book. People are really working hard on making this trek to another world happen. Mars is not that far into the future. Things are actually being developed and created, and the problems are becoming better understood, with people coming up with countermeasures. In the book, I try to show that Mars is not just a NASA-boosted mission, but something the world community can get behind.

You write that the first Mars colonists will have to live off the land. It seems such a barren place. How will they draw sustenance and shelter from such an environment?

The best thing that’s happened in the last few years are the many Mars robotic spacecraft that have flown by, crashed into, are in Mars orbit now, and those that have successfully landed… there’s been a huge retinue of robots going, and those landers, particularly NASA’s Curiosity rover, [have] done a good job of understanding and analyzing the Mars terrain.

Resources are there, pockets of underground ice. One thing that’s missing is a much better accountability of where those resources are and understanding if you land somewhere, how far it is to get to resources, such as water ice. NASA is trying to push for a new orbiter for Mars that would have a powerful radar system on board, one that would look at charting where the resources are. With that information in hand, we would have a much better idea of where to plant the first crew to step foot on the planet, and at least have a fighting chance to start doing some early testing of how best to utilize available resources.

We’ll get those resources charted, make Mars cough up a little more info on these recurring slope lineae, those little gully washes, or whatever they turn out to be, potentially free-flowing water. Some of the people I quoted in the book suggest they may tie to aquifers, and if we’ve got aquifers, then there’s a ballgame change there.

But it also sparks the question, if there’s water is there life? That’s at least one of the compelling reasons we’re going, that search for life. I focus on that topic in the book, the prospect of detecting life on Mars. Is that life a second genesis? Are we worried that Martian life may be hazardous to Earth biology? How do we handle it? How do we even investigate it?

The primary need for any off-world mission is access to water. On Earth, that basic need is growing ever more difficult to meet. How could exploration of Mars inspire solutions to water needs on our home world?

It looks to me like it would, when I look at the hardware that we’re going to have to develop. We’re not going to Mars for spinoffs. But with Apollo we had environmental sensors that had to be developed. There’s a whole litany of things that came out of the space program and particularly human spaceflight that transformed biomedical and detection capabilities. We’re not going to Mars to get spinoffs, but I do think we’ll see developments in water quality and mining. For example, you have the problem of getting heavy machinery to Mars, we’re going to have to lighten the load on that.

I’ve also been getting a number of new papers from people working hard on separation technologies. I don’t want to hype it too much, but I don’t see why we couldn’t expect new filtration systems, life support concepts. Add to that our need to get equipment that doesn’t weigh too much, and can run on its own for a long period of time, and that’s fixable — solar panels, that kind of thing.

Andy Weir’s The Martian — and Matt Damon’s portrayal showing how trying the Martian environment can be — presented a powerful allegory for managing life on Earth. How does stewardship fit into plans for both Mars and our home planet?

I think there’s a role for stewardship. Any time we’re exploring, we get to explore our own frailties as humans. Any time we’re doing space exploration, we learn about our own psychology and our own ability to care for ourselves and others. The sort of Star Trek things — looking for life, the stewardship of the solar system. It’s really important.

I want to underscore that none of this is easy. Andy Weir did a great job of writing that book, and the movie looked so real. There are people, I’m sure, wondering if they shot that on location. His book is about survival. We have analog sites around the planet that people are climbing into and playing out Mars scenarios. We seem to be training ourselves little by little to go.

But I hope when people close my book they get a much better sense of the philosophical aspects of this, way beyond just the technical of putting a bunch of people in a tin can and having them hunker down on the Red Planet. I do think people will look back from the future and salute this human leap between two worlds, and measure how well we did.

This interview was conducted by Josh Chamot, who writes for Nexus Media, a syndicated newswire covering climate, energy, policy, art and culture.