A Trip Down the Ohio River Shows the Future of the Oil and Gas Industry

Facing falling demand for fossil fuels, companies are betting big on plastic.

Text and photos by Teake Zuidema

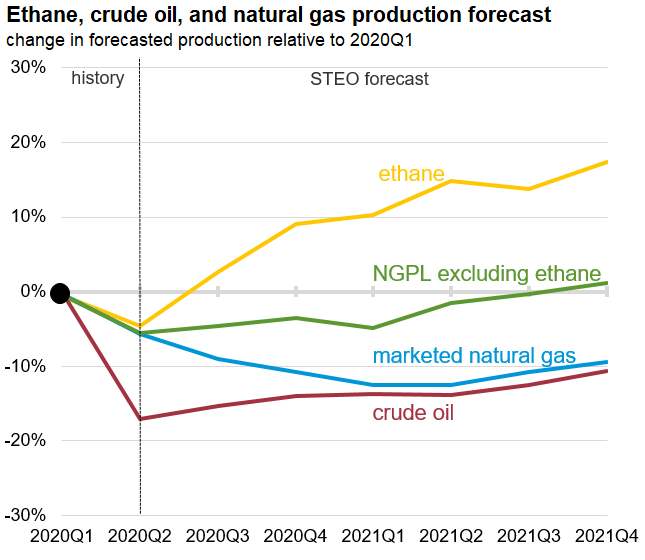

Hit hard by the coronavirus pandemic, Royal Dutch Shell saw its profits drop 71 percent between 2019 and 2020. Its recovery will likely be stymied by the rise of electric cars and renewable energy, which will lead to falling demand for oil and, in the United States, natural gas. There is one bright spot for the industry, however. Ethane, a natural gas byproduct used to make plastic, is projected to be a growth market.

Plastic will figure prominently in the future of the oil and gas sector. A short trip down the Ohio River in Pennsylvania shows what this will look like, and what it will mean for the environment.

In Beaver County, near the Ohio border, a sprawling $6 billion facility of steel and concrete is rising up on the southern bank of the river.

In the next couple of years, this plant, the Shell Pennsylvania Petrochemicals Complex, will use ethane from regional fracking wells to make polyethylene, a type of plastic.

A 98-mile pipeline system will deliver up to 100,000 barrels of ethane per day to the “cracker” plant, which will “crack” ethane molecules apart to produce plastic.

Plants like this will offer a lifeline to drillers. They may be the last best hope for the oil and gas industry.

Beyond buoying drillers in the region, however, the plant may do little to boost the local economy. The construction effort has employed some 7,500 people, though many came from Texas or Canada, and jobs are temporary. The factory will employ only around 600 people full-time.

The plant also promises to generate a lot of pollution.

An WTAE investigation found the cracker plant will be allowed to churn out more pollution than some of the biggest emitters in the state. Its permit allows the plant to produce more than 2 million tons of carbon dioxide each year, as well as more than 500 tons of volatile organic compounds, which cause headaches, nausea and damage to the nervous system. Locals fear the cracker plant will leave a trail of contamination just like the steel mills that came before.

“The pollution we have here was caused by previous plants, and now Shell is coming to add more on top of that,” said Bob Schmetzer, the chairman of the Beaver County Marcellus Awareness Community, a local group opposing fracking. “They will make their money, and then they will pack their bags when the money stops coming in, leaving behind the pollution.”

In addition to air pollution, the plant will generate a steady stream of hard-to-recycle plastic, most of which will end up as waste.

At the Greenstar Recycling plant, just 20 miles south of Shell’s cracker plant, plastic refuse piles up.

The plant used to sell plastic to China before Beijing sharply curbed imports of plastic waste over environmental concerns.

In the United States, less than 10 percent of plastic is actually recycled.

Another 15 percent or so is burned to generate energy.

The rest ends up in landfills.

Because plastic is so polluting and so unpopular, oil and gas companies are also looking for ways to manage plastic waste. Shell joined the Alliance to End Plastic Waste, a group made up mostly of petrochemical companies, which plans to invest $1.5 billion in minimizing plastic waste and promoting recycling. But critics say such efforts are far too meager.

“It’s a trivial amount compared to the costs that are borne by the communities where fracking occurs, waste disposal takes place, and plastics end up in the environment,” said Patricia DeMarco, a Pittsburgh-based environmental consultant. “It makes no sense to produce a plastic bag that is useful for 12 minutes and then remains in the environment for another 450 years.”

Much of the plastic that isn’t burned or recycled ends up in oceans, lakes and waterways – like the Monongahela River, which connects to the Ohio River in Pittsburgh, some 25 miles south of the cracker plant.

Evan Clark, who works for the nonprofit Allegheny CleanWays, drives a boat through the river every day picking up trash. And every day he finds a fresh load of toys, bags, and other plastic detritus in the water.

This is the end point of a system that churns out materials that are difficult to reuse and take centuries to break down.

“It really never stops,” Clark said. “As long as people use plastic, it will end up in the river.”

Teake Zuidema is a writer and photographer based in Savannah, Georgia. He writes for Nexus Media News, a nonprofit climate change news service.