Warren Washington can trace at least one of the origins of his extraordinary scientific career —more than half a century of groundbreaking advances in computer climate modeling — to a youthful curiosity about the color of egg yolks.

“I had some wonderful teachers in high school, including a chemistry teacher who really got me started,” he said. “One day I asked her, ‘Why are egg yolks yellow?’ She said, ‘why don’t you find out?’” So he did. He still remembers the answer — the sulfur compounds in chicken feed become concentrated in the yolk, turning it yellow. “I also had an excellent physics teacher,” he said, describing why he became an atmospheric physicist.

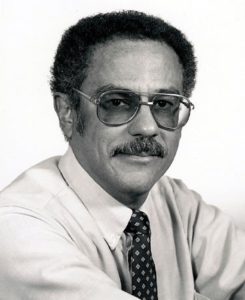

Those teachers would be immensely proud of him today. Before the evolution of sophisticated computers, scientists knew little about the atmosphere other than what they could observe outright. Then a young black physicist came along, eager to use early computers to understand the workings of the Earth’s climate. He collaborated in creating the earliest computer climate models and went on to advise six presidents about climate change — Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush and Barack Obama. He was awarded the National Medal of Science in 2010 by President Obama. Washington, now 82, recently retired after 54 years at the National Center for Atmospheric Research, though it isn’t much of a retirement. He still continues to conduct research as a distinguished scholar.

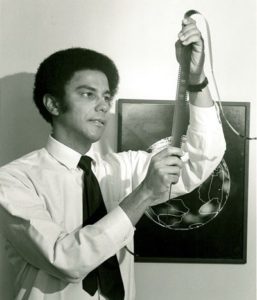

Washington was an early pioneer of climate modeling. Working with Japanese scientists in the early 1960s, he was one of the first to build computer atmospheric models using the laws of physics to predict future atmospheric conditions. Despite his accomplishment, he avoids any semblance of self-promotion and seems happy with his low public profile. “

“I am quiet, but not to the extreme,” he said. “I’m just not as vocal as some people in the field, but that’s OK. [Some] people say I’m a legend, while others joke about the fact that I am still alive.” When compared to the subjects of the movie Hidden Figures, the black, female mathematicians who worked for NASA in the 1960s, he laughed. “You know, I think I met those ladies,” he said, pausing. “It was just a small world then.”

There is no Nobel Prize for climate change, the world’s most pressing environmental problem. But if there were — and there is an ongoing campaign to establish one — Washington almost certainly would be on the short list. He will soon receive the next best thing, the Tyler Prize for Environmental Achievement, often referred to as the environmental Nobel. He will be sharing the honor with climate scientist Michael Mann, director of the Earth Systems Science Center at Pennsylvania State University.

In addition to recognizing their groundbreaking climate research, the award also sends a message to climate skeptics who have gone after Mann and Washington. Mann has endured multiple public attacks and Washington, despite his low-key nature, occasionally fields death threats, which he said “haven’t really had an effect on me.” Washington applauded Mann for standing up to the critics. “He’s handled it very well,” he said.

For his part, Mann is thrilled to be sharing the award with Washington, his longtime idol. “I used to read his papers when I was a graduate student, and he is a real hero of mine,” Mann said, pointing out that Washington received his doctorate in atmospheric sciences — only the second African-American ever to do so — at Penn State. “He is one of our most distinguished alumni,” Mann said. “He is such a great role model, who speaks to the fundamentally important contribution that diversity plays in advancing science.”

Washington’s father, Edwin, was reared in Birmingham, Alabama and attended Talladega College, a small historically black college. After his 1928 graduation, he left the South for Seattle, and a year later for Portland, where Washingon was born and raised. During the Great Depression, jobs were scarce, so Edwin took the only job he could find, as a waiter on the Union Pacific Railroad. “He was bitter about it,” Washington said.

Washington’s mother Dorothy attended the University of Oregon for 18 months, majoring in music. “She couldn’t stay in the dormitory because they wouldn’t allow black women,” he said. “She had to work as a live-in helper for a family to have a place to stay. She left college after two years because she was upset about it.”

In grade school, Washington read books about George Washington Carver and other black Americans “doing interesting science.” By high school, he had decided on a career in physics. But the racism encountered by his parents was still alive at Oregon State University. “My freshman advisor told me I shouldn’t stay in physics because it was probably too hard for me,” he said. Ignoring the advice, he graduated in 1958 with a bachelor’s degree in physics. He then earned a master’s in meteorology in 1960, also from Oregon State, and finally a doctorate in atmospheric science in 1964 from Penn State.

The earliest computer he used — he thinks it was in 1957 — was an old vacuum-tube model, about the size of a room, and agonizingly slow. “In those days it took one day to generate one day of simulation,” he said. Today, “for the highest resolution, we can probably do 10 years in a day. For the lowest, we can probably do 100 years in a day. Today, I probably have more computing power in my smartphone than in those very early computers.”

Most of the presidents he advised — with the exception of Obama — were more interested in supporting climate research than mitigation, he said. President Obama, on the other hand, championed the Paris climate Agreement and crafted numerous climate protections.

Washington first met him in the fall of 2007, when Obama was still a senator. “We both were asked to speak to the Congressional Black Caucus about climate change,” he recalled. “He spoke before me, and it was clear he had read the IPCC report [a major UN report on climate change]. I was next, and I teased him a little bit, ‘You gave my talk.’ He laughed.”

Not surprisingly, Washington has not been asked to brief President Trump, who plans to exit the Paris Agreement and is working to undo numerous Obama-era climate protections.“I can’t figure the man out. He doesn’t get briefings or read. He doesn’t get advice, like most presidents [do],” Washington said. “He doesn’t have any interest in reading any reports on any subject, not just science. During his State of the Union speech to Congress, he didn’t even mention [climate change] once.”

Nevertheless, Washington is encouraged by climate actions outside the federal government, and still has hope for the future. “I think we just have to suffer through another couple of years with this president,” he said. “But I haven’t lost my optimism.”

Marlene Cimons writes for Nexus Media, a syndicated newswire covering climate, energy, policy, art and culture.