It’s hard to imagine feeling a purer joy than American snowboarder Chloe Kim as she flings herself into a 1080, but Olympic athletes aren’t the only ones who love winter sports. In the winter of 2015 and 2016, more than 20 million people took part in downhill skiing, snowboarding and snowmobiling in the United States.

But, there are no winter sports without winter weather, and humans are on track to warm winter into oblivion. Rising temperatures are melting snow, giving winter athletes fewer places to train and compete, according to a new report from climate advocacy group Protect Our Winters. The report found that climate change also threatens to rob the winter sports industries of billions of dollars in revenue.

“Winter is warming. Snow is declining. And that trend hits our communities in the wallet,” said Auden Schendler, a Protect Our Winters board member. “It’s a story that’s playing out all over the United States this very season.” Over the last century, average December through February temperatures have risen by more than 2 degrees F in the Lower 48. The extra heat has hastened snow melt and caused more precipitation to fall as rain instead of snow.

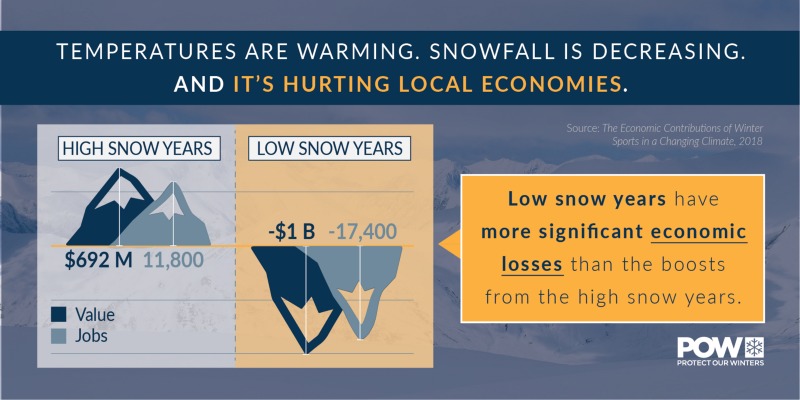

Diminished snowpack is bad for ski resorts, as well as the hotels, restaurants and sporting goods stores that depend on winter sports to turn a profit. The Protect Our Winters report found that a low snow year can cost the economy more than $1 billion and upwards of 17,000 jobs, compared to the average year.

Scientists have chronicled the many ways that climate change is reshaping American winters. In short, the snow’s not doing so hot — or rather, it’s doing too hot. Here are the highlights from the research:

- Less area is covered by snow.

On average, the portion of North America covered in snow has shrunk by an area roughly the size of California since the early 1970s. - There is less water stored in the snowpack.

The amount of water stored in snowpack declined across much of the western United States between 1950 and 1999, and scientists attribute about half of the observed decline to human-caused climate change. - Snowlines are receding.

The snowline is the elevation at which precipitation begins to fall as snow instead of rain. Like many hairlines, snowlines have been receding over time. Scientists observed that warming temperatures pushed the northern Sierra snowline uphill by as much as 1,500 feet in recent years. Now, daytrippers itching for a snowball fight have to drive further uphill. - Less precipitation is coming down as snow.

An analysis of reports from California weather stations located between 2,000 and 5,000 feet above sea level found that snow now makes up a smaller share of total precipitation than it did in the past. - The ‘freeze season’ is shorter.

The U.S. freeze season — defined as the time between the first freeze in the fall to the last freeze in the spring — was more than a month shorter in 2016 than it was in 1916.

Climate change isn’t just taking a toll on skiing and snowboarding. In Minnesota, ponds aren’t freezing as consistently as they used to, threatening outdoor hockey. Alaska’s Iditarod moved its starting line further north in 2015 due to record-warm temperatures.

Around the world, winter sports are struggling to keep up with climate change. In Bolivia, the retreat of the Chacaltaya glacier forced a popular ski resort to close in 2009. Last year in Canada — where winter temperatures have risen more than 4.5 degrees F since 1950 — a leading summer ski camp closed due to declining snowpack. In Switzerland, snow season now starts later and ends earlier than it did in decades past, and businesses are struggling to keep up.

No Country for Snow Men

For a generation, Camp of Champions was Canada’s premier summer training ground for freestyle skiers and snowboarders — then it melted away.

“I’ve spoken to people in Switzerland who are losing their jobs because winter’s going away,” cross-country skier Jessie Diggins told The New York Times. “Over the last 10 years, it has been hard to ski on real snow. Over the last three years, most venues have been exclusively on man-made snow.”

Athletes and spectators worry how climate change will impact the Winter Olympics. By 2050, nine former host cities may not be reliably cold enough to host the Games — including Sochi and Vancouver. Already, many athletes are having to travel increasingly long distances to find suitable conditions, often to different continents, as longtime training grounds wither in the heat.

“I can see a huge difference,” French skier Ben Cavet told the Associated Press, describing his usual summer training site. “Up on the glacier, now there’s this huge cliff, you know like a big rock, that you couldn’t even see before.”

Celia Gurney writes for Nexus Media, a syndicated newswire covering climate, energy, policy, art and culture. You can follow her @celiagurney.