A healthy coral reef sounds like a bowl of Rice Krispies in milk. Snap. Crackle. Pop.

“Thousands of invertebrates make this constant crackling, sizzling, static-like sound as … shrimp snap their claws and sea urchins scrape over rocks,” said scientist Tim Gordon. “Punctuated throughout that, you can hear the grunts, whoops, and chatter of many different fishes.”

A dying coral reef, on the other hand, makes no sound at all.

That’s a significant problem if we hope to revive reefs laid to waste by ocean heat waves. So Gordon, a marine biologist at the University of Exeter, designed a novel experiment he hopes will help bring dying reefs back to life: use underwater loudspeakers to play real sounds of flourishing reefs to fool the fish into returning. He thinks he might be able to lure young fish to the now barren landscape, where they will make new homes and begin to restore the reef.

“Once they’ve chosen a place to settle and live, they tend to stay there,” Gordon said. “That means if we can persuade them to settle somewhere, and they’re able to survive, they are likely to stay put. That’s good news for reef restoration”

The researchers placed speakers playing sounds of healthy reefs in dead patches along Australia’s Great Barrier Reef and found that twice as many fish showed up in those areas as compared to places without speakers, or where the speakers were silent. Their findings were published in the journal Nature Communications.

Gordon’s group has studied reef sounds for years, aware that many creatures begin their lives in the open ocean and then listen for the usual sounds of a coral reef to guide them to a permanent home.

“Just like birds in a forest, fish on a reef have a dawn chorus, a dusk chorus, and different sounds in the day time and the night time,” Gordon said. “There is a daily ebb and flow of the rhythm of the reef.”

But as reefs succumb to super-powered typhoons and ocean heat waves made worse by climate change, this daily symphony dies. All goes quiet.

“This is tragic to hear, and also concerning — without these sounds, there’s a real danger that fishes can no longer hear their way home,” Gordon said, citing an earlier study he and his colleagues conducted that confirmed this.

This is important because each of the fish living on coral reefs plays a key role in maintaining a thriving habitat. Predators keep plankton-eating fish from growing too numerous. When waves sweep plankton onto reefs, plankton-eating fish devour them, and they in turn are eaten by larger fish. At the same time, herbivores keep the abundant algae growing on degraded coral rubble from overtaking the reef, ensuring there are bare places for coral to grow.

“For a healthy reef, all of these different members of the community are important — and excitingly, our study found that fish in all levels of the food chain could be attracted by sound,” Gordon said.

To conduct the experiment, an international team of scientists — which included researchers from the University of Bristol, Australia’s James Cook University and the Australian Institute of Marine Science — used recordings of parts of the Great Barrier Reef from five years ago, when those areas still were “vibrant, colorful, noisy cities of the sea,” Gordon said. They gathered more than 2,000 pounds of dead coral rubble to create 36 experimental areas, and set up underwater loudspeakers to make them sound like healthy reefs.

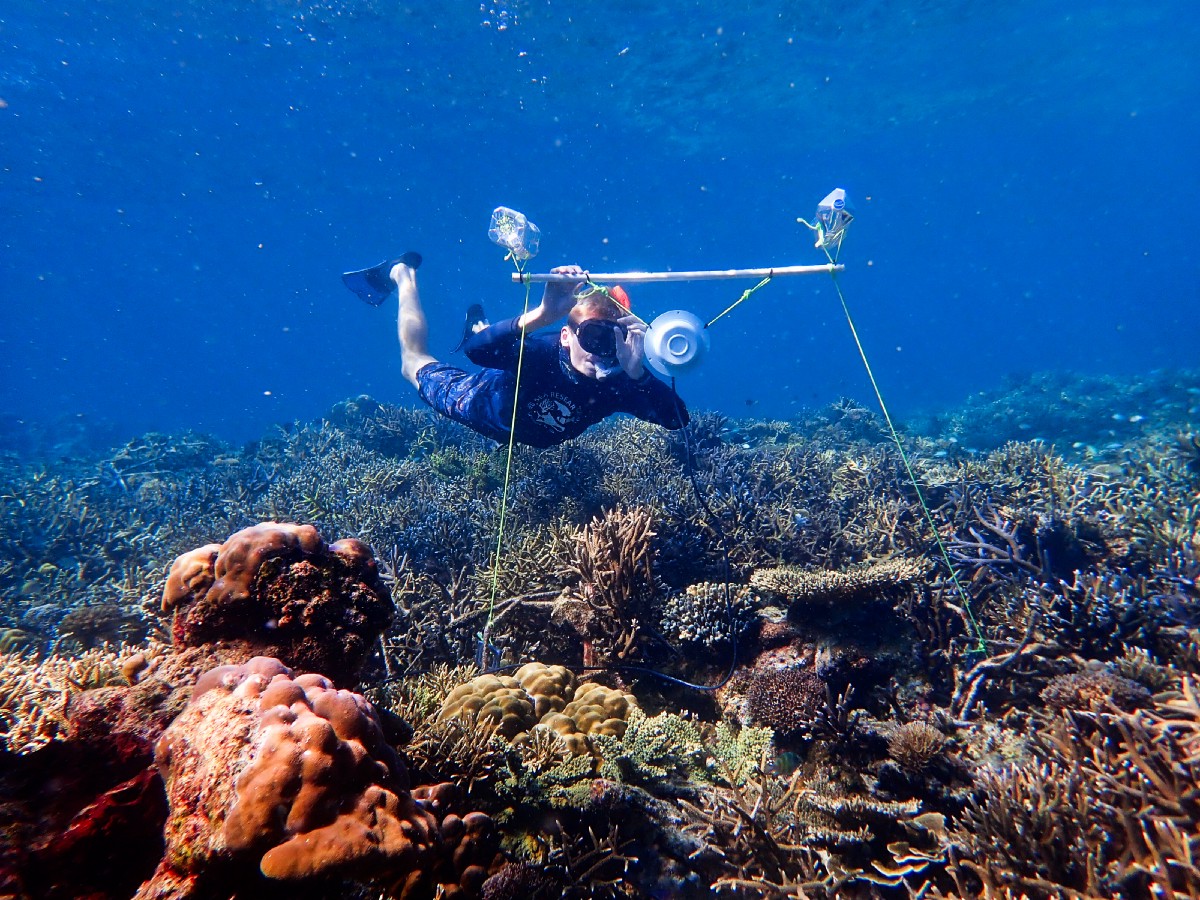

“We put the batteries and MP3 players that drive these speakers in waterproof barrels floating above the reef, and tied the speakers to the habitat patches themselves,” Gordon explained. For comparison, they placed soundless speakers — or no speakers — at other spots. Then they monitored them to see what fish turned up to settle there.

“For six weeks, two of us put on scuba gear and made regular visits to each reef, recording the fish that we could see settling on the reefs, without ever getting too close — we didn’t want to disturb the developing communities,” Gordon said. “Then at the end of the experiment, we really carefully examined every single piece of rubble one-by-one to get a really comprehensive survey of all the fish on the habitat — even the ones that hide away in the rubble that you’d never normally see.”

At the start of the study, the reefs were empty piles of rocks. But “by the end, many of them had thriving communities of many different kinds of fish on them,” Gordon said. “Watching those communities grow and develop throughout the experiment was really encouraging.”

Ravi Maharaj, a researcher in ecology and marine biology at the University of British Columbia — who was not involved in the study–called the research “a novel, readily deployable method for boosting restoration efforts.” He added that the findings could help guide fish who are finding it harder to smell their way around as carbon pollution turns oceans more acidic.

However, Maharaj cautioned that the sound cues could fall short of their goal if they couldn’t attract sea life from up and down the food chain. Juvenile fish that feast on mollusks, for example, might not stick around if they can’t find enough prey.

From Gordon’s point of view, sound baiting is only one promising tool. It needs to be combined with other conservation measures, such as curbing water pollution and overfishing, as well as actively restoring ocean habitats, he said. And critically, he said, humans have to rein in climate change.

“No reef restoration can work without simultaneous dramatic action on carbon emissions to reduce global warming and prevent further damage,” he said.

Marlene Cimons writes for Nexus Media, a syndicated newswire covering climate, energy, policy, art and culture.