From hurricanes bearing down on Florida to megafires burning in the West, the climate crisis seems to be everywhere, all at once. But on TV and film screens, mentions of climate are far rarer.

A study by the University of Southern California’s Media Impact lab examined more than 37,000 film and TV scripts that aired in the U.S. between 2016 and 2020. It found that only 2.8 percent even mentioned climate-adjacent words like solar panels, fracking, sea level rise or renewable energy.

“We know that’s really low for a phenomenon that we are all experiencing,” said Anna Jane Joyner, founder of Good Energy, a nonprofit consulting firm. The group has a goal: to get 50% of television and film scripts to touch on the climate crisis by 2027.

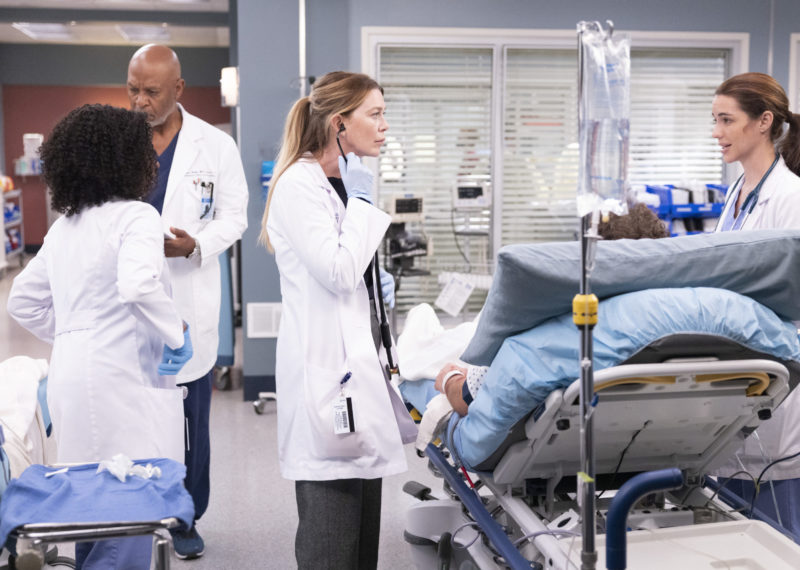

A growing number of shows are incorporating climate themes, Joyner said. Last season, the ABC hospital drama “Grey’s Anatomy” aired an episode called “Hotter Than Hell,” based on the real-life heat dome that baked the Pacific Northwest the previous summer. “When the body’s exposed to rising temperatures, it has the ability to cool itself down. We sweat, our blood vessels dilate, and our heart rate increases,” Meredith Grey, the show’s titular character, narrated. “But when the temperature starts to inch above 100 degrees, our bodies have to work overtime, leading to heat exhaustion. We become nauseated, dizzy, and confused.”

The upcoming Apple TV+ anthology drama “Extrapolations”, starring Meryl Streep, Edward Norton and Marion Cotillard, is billed as an exploration of “how the upcoming changes to our planet will affect love, faith, work and family on a personal and human scale.”

Hulu’s Indigenous American teen comedy-drama “Reservation Dogs” features Dallas Goldtooth, an advocate with the Indigenous Environmental Network and includes references to the Land Back Indigenous sovereignty movement, which is part of a wider climate justice movement.

On ABC’s “Abbott Elementary,” Principal Ava complains about a “February hotter than the devil’s booty,” to which a colleague replies: “Climate change. We are living in the middle of its disastrous effects.”

“[The climate crisis] is such a part of our global and individual experience, and that’s only going to become more so in the next decade,” Joyner said. “Eventually it’s going to be an intentional creative choice to not include mentions of climate change, and stories will feel outdated if they don’t acknowledge this is part of our world now.”

Research shows that people tend to underestimate how much others care about climate change — they think they care more than their neighbors or family members. While 70% of American adults say they are “concerned or alarmed” about the climate crisis, they’re not talking about it – only about one-third reported discussing the topic with their friends or family.

That creates a sense of isolation and anxiety, Joyner said. “Television and film can do a lot to assuage that because it validates the audience’s own experiences and feelings.”

That means that climate storylines can be comedic, absurdist or dramatic. In fact, Joyner said she finds doom and apocalypse plotlines to be limiting. “People need more stories about the future we do want,” she said.

Showing that climate change is something that is real, and happening now can galvanize audiences to act, said Max Boykoff, a researcher at the University of Colorado Boulder who studies climate change communication. “Even in the last few years, we’ve been seeing this more and more – not just futuristic portrayals that are talking about climate change, but showing where we live and what’s going on right now,” he said. “This isn’t just about sacrifice. This can be about innovation, it can be about opportunity, it can be about actually having fun.”

Victor Quinaz, a writer and producer on Netflix’s “Big Mouth” and “GLOW,” said it’s not always easy to bring up the climate crisis in a pitch meeting. “I don’t think I would ever go into a room and pitch, ‘this is about climate change’,” he said. “That is such a pitch-killer. I think we have to be far more subtle about the storytelling.”

On “Big Mouth,” Quinaz said his team consulted neuroscientists, psychiatrists and other experts to understand what kids were feeling during puberty – and one predominant emotion was anxiety. Climate anxiety is a major stressor among young people and something Quinaz weaves into storylines: on one episode, Andrew Glouberman’s family visits Florida, when a massive sinkhole opens up and devours the west coast of the state.

Quinaz is currently developing a show with Jenji Kohan (“Weeds”, “Orange is the New Black”) based on his experiences as a disaster relief volunteer. “For me, the story wasn’t about climate change, it was about how we help people in this time period, and the anxiety of living through this time,” he said.

Dorothy Fortenberry, a writer and producer on “Extrapolations,” said she sees more interest in climate plotlines in Hollywood. “Just in the last five years, I’ve been a part of many more conversations about how to bring an awareness of the complexity of climate change to the show they already want to write,” she said. “People are asking: where’s the climate part of that show?”

Fortenberry points to short climate mentions – in Shen Weng’s new Netflix standup special, the comedian leans into a joke about climate change and then moves on. “It doesn’t feel like pausing and doing a Very Special Episode, it doesn’t feel like you leave the narrative world,” she said. “It’s not like a 90s sitcom that suddenly needs to talk about bulimia for 26 seconds.”

She hopes that climate stories will be ubiquitous – but also multifaceted. “If all the climate stories are the same, and the same type of view, it will be boring and bad,” said Fortenberry. “My hope is every creative person takes this in the direction that is fruitful for the narrative and we end up with a real panoply of narratives.”

Nexus Media News is an editorially independent, nonprofit news service covering climate change. Follow us @NexusMediaNews.