As a Harvard graduate student, Sarah Fankhauser judged a science fair at a local high school. She was thrilled to see the students’ work, but when she walked outside, she noticed that many of the projects ended up in the dumpster.

Disheartened by the less-than-grande finale, Fankhauser came up with a novel idea — what if middle and high school students could share their work beyond the school auditorium? In 2012, she launched The Journal of Emerging Investigators (JEI), a non-profit, peer-reviewed scientific publication for K-12 students. She wanted to give aspiring scientists the opportunity to submit original research, work under the guidance of a mentor, receive critical feedback from Harvard-trained researchers and publish their work for free. Since its debut, JEI has received 350 student submissions and published 103 of them.

“Being able to interact with these younger students…there’s an innate sense of satisfaction, like we’re really mentoring the next generation of scientists,” said Fankhauser, who now teaches biology at Emory University.

While JEI sustains itself with minimal funding from Harvard University, other science-forward education initiatives are currently under threat. President Trump’s new budget proposes billions of dollars of cutbacks in research and education, including a $900 million hit to the Department of Energy’s Office of Science. NASA’s Office of Education, which funds the space camp program, along with approximately 50 other science education initiatives for students, is also on the chopping block. Many students, particularly those from low-income communities, could be deprived of science education.

In the current environment, JEI’s president Mark Springel believes academics need to bolster science education. “I think our hope is that JEI and other organizations like us are part of a new push to try to increase appreciation of science,” he said.

In addition to recognizing students for their work, Springel said the program nurtures critical thinking skills. “We’re increasing science literacy for these kids… [they’re] realizing that science isn’t black and white. It’s very nuanced, and that’s part of the beauty of science, that it’s a way of thinking and critically tackling problems, as opposed to just remembering a set of facts,” Springel said.

Training students in evaluation and inquiry isn’t just an asset for school science fairs. It’s critical to the health of a democratic society. “We’re molding young students to understand that science is a way of thinking,” added Fankhauser. “I think it’s incredibly important to build up the next generation to understand science, to understand inquiry and to appreciate it. In ten or 15 years, we’re going to have a population that supports science, and hopefully they will be voting.”

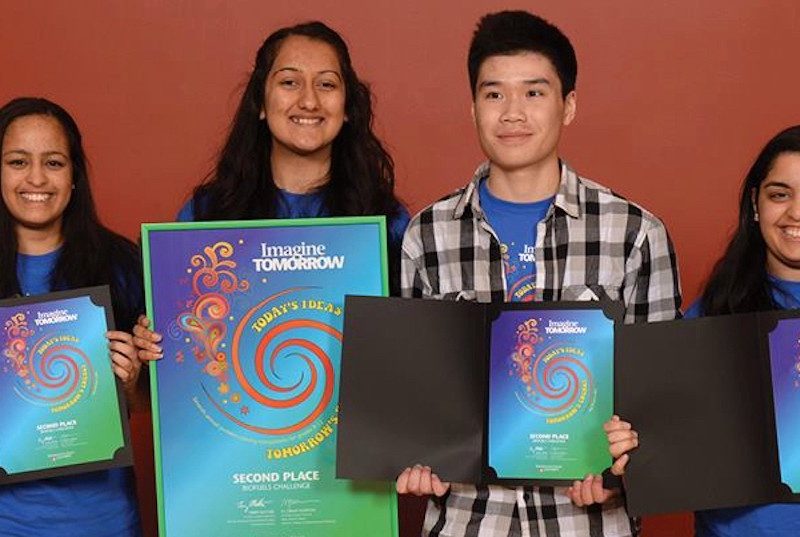

So just who are these bright young minds? We spoke with five of the students who benefitted from JEI’s program: Honson Ling, Jyoti Bodas, Simreet Dhaliwal and Aarti Bodas, who published a study on turning biowaste into biofuel, and Hugh Han, who authored a study analyzing climate change using historical weather data.

Now college students, they are continuing their science education in the hopes of developing solutions to climate change. Drawing inspiration from teachers, family members and the natural environment, these young adults are changing the face of science, all before an age when they’re even allowed to drink. And when they’re not tackling complex global issues, they like to have a bit of fun, too.

Honson Ling, 19, a sophomore at the University of Washington, Seattle, changed his major from biology to a double major in psychology and sociology after discovering his passion for studying human behaviors, interactions and social structures.

“I remember in 6th grade, my science teacher showed us a documentary film on electric cars. His immense passion for environmental effort was what first inspired me to be involved in the issues of climate change. His mentorship made our team feel like it was possible for even high-schoolers to tackle the crisis of climate change.”

Jyoti Bodas, 20, studies environmental science and resource management at the University of Washington, Seattle. She believes that fearlessly asking questions, reflecting and appreciating the world around you is the key to being who you want to be.

“I think the biggest challenge [with our research] was waiting for months for results and, if they came back negative or things weren’t going according to plan, going back to the drawing board. But this played into one of the biggest lessons we learned, which was, that our technology and methods need to fit nature’s system.”

Simreet Dhaliwal, 19, is a bioengineering student at the University of Seattle, Washington. In her free time, she likes to read — particularly the Harry Potter series — bake, swim and watch movies.

“Learning in school can sometimes feel forced and students may feel that they are spending time on something they do not love. Learning through an experiment like this has never felt that way. Sure we felt frustrated at points, but these setbacks always made us want to bounce back harder than before. Moreover, getting credit for our work is one of the things I am most proud of.”

Aarti Bodas, 20, is a currently a student at the University of Washington, Seattle, where she is pursuing a degree in psychology and global health. When she is not thinking about the health risks of climate change, she likes to blog on both Medium and her personal website.

“Our research, findings and conclusions made me realize that to solve difficult problems like that of climate change, it is essential to get creative in finding and using resources, and sometimes the most ideal resources can be found in places you might never think to look.”

Hugh Han, 20, is pursuing a combined bachelor’s and master’s degree in computer science at Johns Hopkins University. Han is so interested in data science and machine learning, that he is already contemplating his PhD!

“My biggest inspiration has always been my father. Growing up in a small village in communist China, he was the son of a factory worker and farmer. Pretty much everyone was poor at the time — eating three meals a day consisting solely of congee and some pickled vegetables was standard; eggs were had around twice a week. He worked hard throughout primary and secondary school to be admitted to Tsinghua University, a top university in China. After completion, he and my mother immigrated to the US, where he simultaneously pursued his PhD in Physics and worked two minimum wage jobs to get by.”

Laura A. Shepard and Monika Sharma write for Nexus Media, a syndicated newswire covering climate, energy, policy, art and culture. You can follow Laura at @LAShepard221.