There is wide-eyed, furry-faced, newborn bison making headlines. In his infinite cuteness, he is teaching us an important lesson about nature.

Last week, a pair of visitors to Yellowstone National Park took a newborn bison to park authorities because they said it looked cold. After it made contact with humans, the calf was rejected by its mother, forcing park rangers to euthanize the animal. The story broke just one week after President Obama signed a law declaring the bison our new national mammal.

This is hardly the first instance of a well-meaning individual upsetting the delicate balance of nature. Countless men and women blessed with compassion, forethought and ingenuity have, in the absence of warnings from experts, turned ecosystems inside out.

Kudzu, a fast-growing Asian vine, entered American gardens as an ornamental houseplant at the end of the 19th century. When the Dust Bowl hit, the US Soil Conservation Service enlisted the vine to guard against erosion. While kudzu slowed the loss of topsoil, it also overwhelmed surrounding plants and blanketed landscapes. The so-called “the miracle vine” was renamed “the vine that ate the South” and became the poster child for invasive species in the United States.

The South American cane toad arrived in Australia in 1935 on a mission to eradicate the swarms of beetles ravaging sugar cane crops. While they failed to vanquish the beetles, the toads gained an ecological foothold, displacing native reptiles as they spread across the country. Today, Australian cane toads number in the billions.

DDT played a key role in fighting vector-borne diseases like typhus, malaria and dengue fever during World War II. It was later revealed that the insecticide imperiled wildlife — it nearly eliminated the American bald eagle. DDT was also linked to infertility and birth defects in humans and, in 1972, it was banned by the Environmental Protection Agency.

Time and time again humans have demonstrated an almost preternatural ability to mismanage nature. Good intentions gone awry have had disastrous outcomes. Never have these stories been more relevant than today.

The ecological challenges of the 21st century surpass any that came before. Climate change and ocean acidification belong to the Anthropocene — the name scientists have given our current epoch in which no ecosystem lies beyond human touch. Ill-conceived fixes to our current environmental calamities won’t just leave us with a surplus of sticky South American toads. They could prove catastrophic for human life.

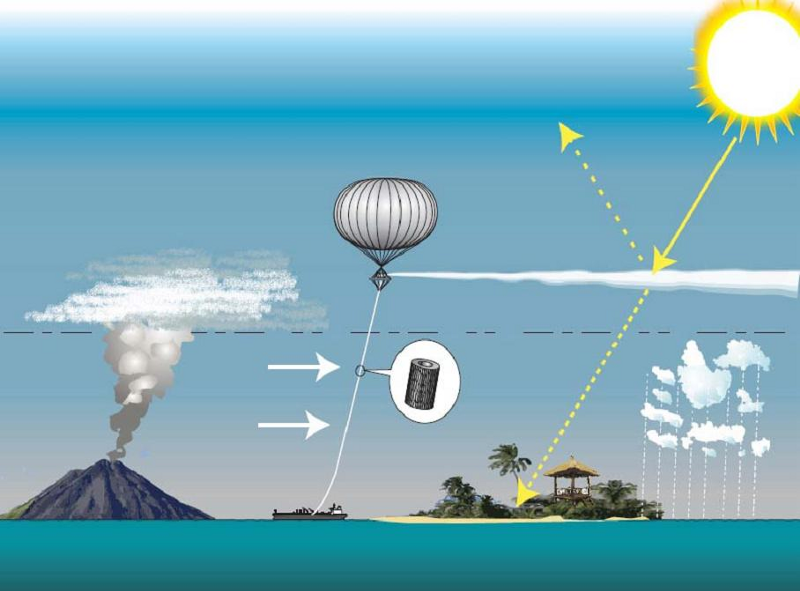

The carbon crisis has inspired a range of madcap schemes to rejigger the Earth’s climate to slow or even reverse the warming trend. One plan calls for spraying sulfur dioxide into the upper atmosphere to block sunlight and halt the rise in temperature. A team of UK scientists warns the proposal would lead to widespread drought, harming billions of people. Oxford physicist Raymond Pierrehumbert has called the idea “wildly, utterly, howlingly barking mad.” And yet the plan has found supporters, among them Bill Gates and Richard Branson.

So appealing is a quick fix that the risks are obscured by any imagined upside. Blocking sunlight won’t alleviate air pollution or stem ocean acidification. It may slow warming, but it may also be the next, and last, in a long list of environmental follies.

The hazards of the Anthropocene invite us to make riskier bets with more chips. But, if history is any indication, humans should play more conservatively and, where possible, consult their local scientist.

Jeremy Deaton and Mariya Pylayev write and produce videos for Nexus Media.