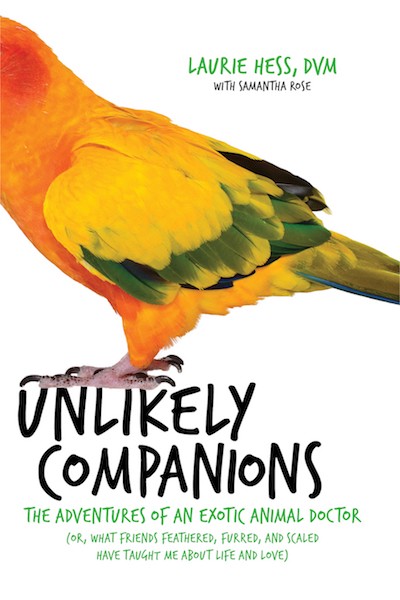

Even blue-throated macaws and radiated tortoises sometimes need a doctor. Veterinarian Laurie Hess catalogued her decades spent treating unusual creatures in her new book Unlikely Companions: The Adventures of an Exotic Animal Doctor. Recently, she spoke with Nexus Media about exotic animals — which to adopt, which to avoid and which are most threatened by humans. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Almost every pet I see is completely different from a dog or cat, with different requirements. I see sugar gliders and parrots, guinea pigs and chinchillas, hedgehogs, potbellied pigs, degus. All kinds of reptiles — snakes and lizards, bearded dragons, geckos, iguanas. But we also see some odd things.

In the book, I talk about a Nile monitor, a very large lizard, and we have the occasional really odd thing, like a wallaby. The wallaby was raised by a young stockbroker, and he had taken all of the precautions to keep the animal safe. Even though he had walls built around his house, the animal got out — it’s been spotted over many years now hopping around Westchester County.

I was convinced the animal had died in the wild, because it really didn’t know how to feed itself, and I’m not convinced that it hasn’t passed away, but supposedly, the police saw it the other day. They say they followed it in the wild with infrared cameras. I don’t know. Wallabies are adorable, but they’re big animals, and one can hurt you if you don’t know what you’re doing.

Some animals that show up in vets’ offices are on the threatened or endangered species lists. Many, especially where rainforests are disappearing, are facing disaster. Fungal and viral diseases, invasion of non-native species that are predators, pollution and environmental toxins, medication in water running off populated areas — leading to antibiotic resistance— all of these factors threaten species and their environments.

There’s also more agriculture being developed, leading to clearing of land and trees. A lot of birds need nest sites, and so do reptiles and amphibians — birds typically in or on trees or on the ground, reptiles and amphibians usually on the ground or under the ground where there’s water. They hide in brush, and with clearing of trees and destruction of water bodies, they can’t have a proper nest and can’t breed. They also can’t hide from predators, so they get captured, and when they are exposed to elements — whether cooler or warmer temperatures — they may become more susceptible to infection.

With reptiles, I had an experience a number of years ago when a man came in with seven radiated tortoises that happened to be — the week before — on the cover of National Geographic because they are critically endangered. The man meant well. He said he was part of a breeding program with the Bronx Zoo, but he had no paperwork to prove it. So, I ended up having to call the New York Department of Environmental Conservation, and they took the tortoises away and fined him. He was well-meaning, but he just didn’t understand that this was a very serious thing.

A few years ago, I had a woman bring in two blue-throated macaws, which are critically endangered species. The woman had picked the birds up in Queens at a pet store where they were sold as blue and gold macaws, which are fairly common. Blue-throated macaws look kind of similar, but have a blue patch under their neck and are smaller than the blue and gold macaw. I advised the woman to contact the pet store about their confusion and recommended that she contact the local zoo about her new pets.

I was reading a story recently about Tony Silva, an aviculturalist who was associated with Loro Parque, a huge parrot rescue organization. In the late 1990s, he was the person campaigning to “save the birds.” Meanwhile, he was running a smuggling ring, and he made millions and millions of dollars. This was someone who was touted as the guy who knew everything about parrots and rescue and so on. There’s still smuggling going on, and there’s poaching that you can see with many species, not just pet species. It’s a huge problem, particularly with the perceived medicinal value of some of these pets for some people.

The good news is that all of the birds I see now in captivity — they were born here. And they’re different these days — we’re seeing a lot more smaller pets, such as cockatiels, parakeets, conures and caiques, and not so many big Amazons or macaws. There are strict laws that prohibit the importation and smuggling of parrots, a problem for numerous species.

There are also animals too dangerous for people to have as pets. We won’t see venomous reptiles in my practice — I don’t think they have any place at all in a home or a pet setting, as they can kill you. For the same reason, I’m also not a fan of primates. They carry serious diseases, ones we are vaccinated for as children.

There are a lot of primate species, like chimpanzees, that people want to adopt and make into child substitutes, and they’re not. When they become sexually mature — and if they’re large enough, like in the case of that woman with the chimpanzee in Connecticut — they get frustrated sexually and they will attack you and cause horrible damage.

People don’t understand that, just like a child going through puberty, the same thing happens with other primates. And you can’t really reason with these animals. It’s not their fault. They didn’t ask to be held captive.

Such misinformation about exotic pets is a huge problem. We veterinarians talk about ‘Dr. Google’ all the time, as there’s a ton of misinformation about exotic pets online. It can keep people from bringing their exotic pets to the vet, because they don’t even know that these animals need veterinary care. Too often, people don’t bring their exotics in until they’re on death’s doorstep, and the owner has tried 16 things online that are completely outdated and no longer applicable.

My goal in writing Unlikely Companions, and in a lot of things that I do in my practice, is to teach people how to find the right information about exotics and provide trusted resources. The Association of Avian Veterinarians, the Association of Reptile and Amphibian Veterinarians and the Association of Exotic Mammal Veterinarians are three groups to which all exotic vets belong, and where we all share our resources.

Exotic pet owners take these animals that evolved in a certain way and put them in a completely different setting. Right now, I’m looking out my window in the Northeast, and there’s a foot of snow. These animals are in foreign climates, in foreign environments. They don’t even have the same vegetation they would normally be eating in the wild. So, the message I always share is that if you’re thinking of getting an exotic pet, you really, really need to decide if you can provide it with the things it requires. That means the right food, the right temperature, the right light. Think it through — when housed and fed the right way, according to the animal’s needs, these pets can thrive and make terrific companions for many years.

Dr. Laurie Hess is an avian specialist and author of Unlikely Companions: The Adventures of an Exotic Animal Doctor. This interview was conducted by Josh Chamot, who writes for Nexus Media, a syndicated newswire covering climate, energy, policy, art and culture.