“The clearest way into the Universe is through a forest wilderness,” said John Muir. America’s first great naturalist worshipped at the altar of the American wilds, where oaks and redwoods buttressed a vast cathedral. This, believed Muir, was where one could commune with the Almighty. But what happens when the temple begins to crumble?

In this summer of record heat, roughly 30,000 firefighters and their staffs are battling wildfires across the country. Fires have incinerated 3,000 acres of Washington’s North Cascades National Park, 4,000 acres of Montana’s Glacier National Park, and 5,000 acres of the Sequoia National Forest, which borders John Muir’s beloved Sequoia National Park. Climate change is fanning the flames with early snowmelt, hotter summers, and historic drought. Today, fire season lasts 78 days longer on average than it did in 1970.

In years past, wildfires have wreaked havoc on the budget of the Department of the Interior and, by extension, the National Park Service. For national parks, that has meant reduced funding for maintaining trails, restoring habitats or aquiring new lands. Parks all over the country have been affected. “You might be borrowing funds from a trail maintenance project in New York that has nothing to do with a fire in Montana,” said Ani Kame’enui, Director of Natural Resource Policy at the National Parks Conservation Association. As a result, nature lovers have been left with less healthy, less expansive, less well-maintained parks.

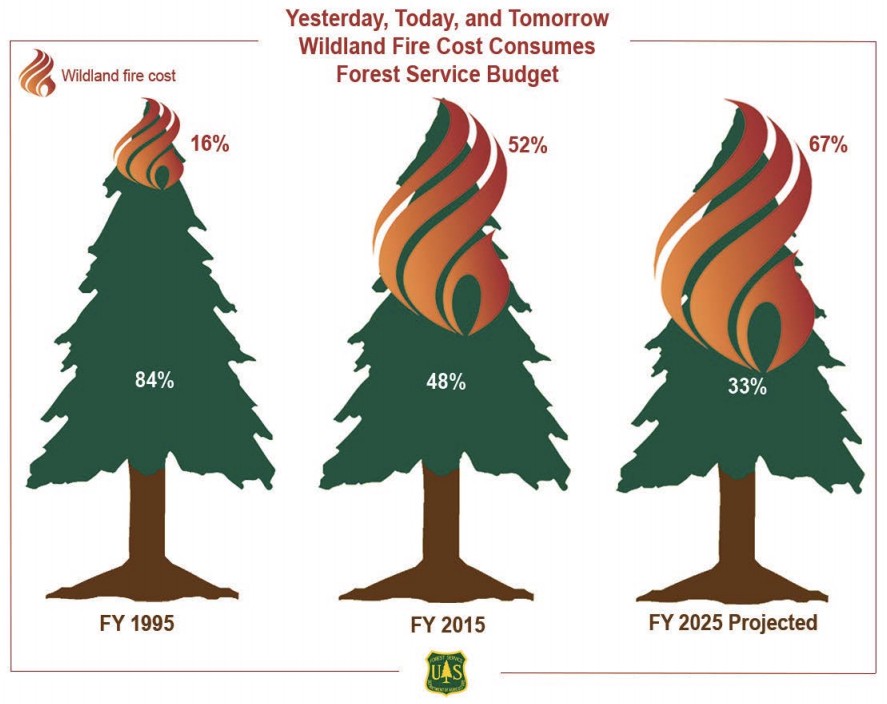

The problem is that fighting fires is an extremely costly endeavor. “You’re seeing a lot of funding going into fighting fire both on park service lands and forest service lands,” explained Kame’enui. In 1995, fire accounted for 16 percent of the Forest Service’s budget. This year, fire has eaten through more than half of the agency’s resources.

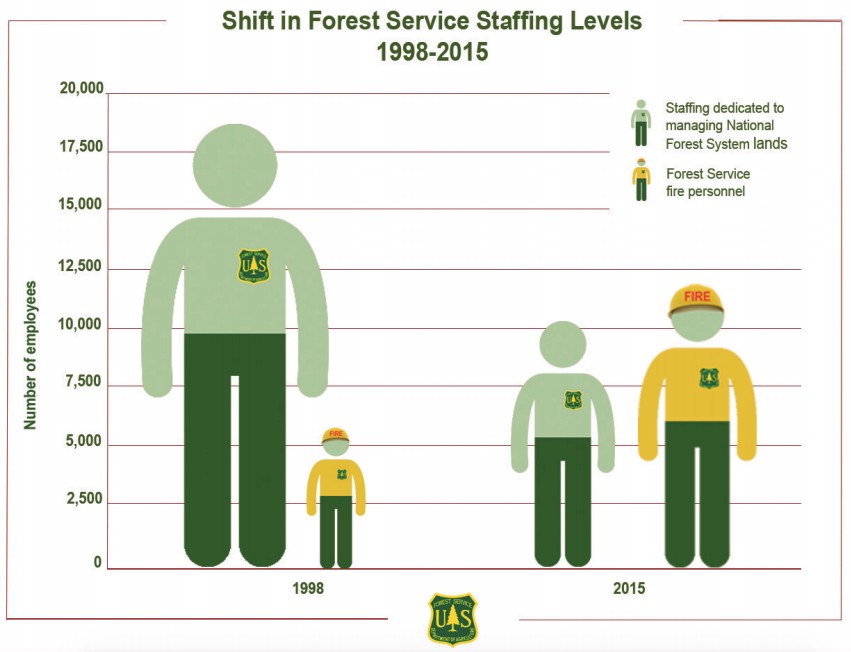

Since 1998, the number of fire personnel employed by the Forest Service has more than doubled, while the number of staff dedicated to managing forests has been cut nearly in half. The agency has become more about fighting fires than about forest management.

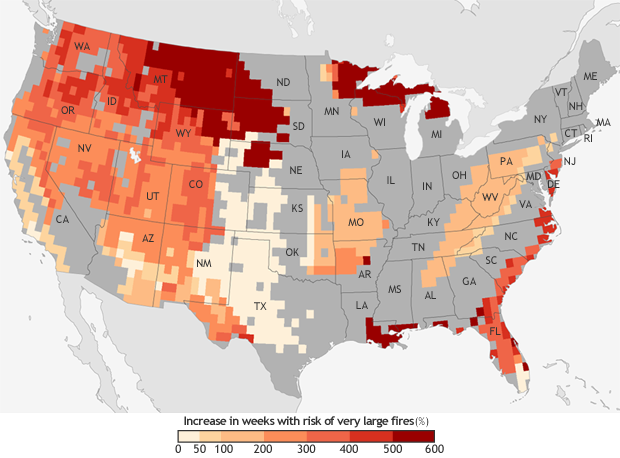

This problem will likely only get worse in the coming decades. NOAA predicts climate change will increase the potential for the largest fires, both by extending the fire season and by contributing to the conditions —dry weather and warm days — that ignite the most ravenous infernos. In some parts of America, the number of weeks during which the conditions are ripe for very large fires could increase six-fold by mid-century.

The only thing that might be more notable than the rising fiscal cost of wildfires is the experiential cost. Fires deprive national park visitors of the opportunity to behold our most sacred treasures. Smoke obscures vistas and threatens the health of anyone within reach. “Glacier National Park — my family lives right outside of the park. My sister goes annually to visit from Seattle, and they’re not going to go because it’s too smoky,” said Kame’enui. She added that, as the climate gets hotter and drier, “We’re going to see more iconic landscapes and more iconic places within these landscapes affected by fire.”

Even in some places where wildfire benefits wildlife, fires have become a predicament. “Sequoia is an interesting place because that ecosystem depends on fire,” explained Kame’enui. “The problem is that we’re seeing bigger fires and more frequent fires than that ecosystem can really maintain in a healthy fashion.”

This week marks the 99th anniversary of the National Park System, a moment of reflection for park enthusiasts. Many of our most beautiful forests have survived for centuries, enduring drought, storms, floods, disease and avalanches, and yet now they stand at risk from ever more voracious wildfires. These fires threaten our home. They threaten our temple. They threaten, as Muir wrote, “our way into the Universe.”

Jeremy Deaton writes for Nexus Media, a syndicated newswire covering climate, energy, policy, art and culture. You can follow him @deaton_jeremy.