In the normal course of business, healthy companies succeed and sickly companies fail. But the coronavirus has interrupted the normal course of business, putting even successful firms on life support as they struggle to pay for sidelined workers and shuttered storefronts. The government’s goal, in theory, should be to keep these companies alive without lending a dime to firms that were already going under.

The Federal Reserve could fall short of this aim, however, by giving a jolt to fossil fuel companies that were failing before the coronavirus. Through its recently announced debt buyout programs, the Fed may aid energy companies whose financial woes predate the pandemic by at least half a decade.

“If you listen to the oil industry, you might think that its crisis began in March, and that’s what they want everyone to believe,” said Clark Williams-Derry, an analyst at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis. “They want everyone to forget about the last six years.”

Over the last decade, fracking unlocked new reserves of oil and gas. For a time, business seemed promising. But as firms flooded the market with cheap fuel, prices began a swift and precipitous decline, dropping from more than $100 a barrel in 2014 to around $30 in 2016. The market never fully recovered. Oil and gas companies took a hit and — because low-cost natural gas edged coal off the power grid — mining companies did as well.

“Fracking has literally broken the business model of the entire fossil fuel sector,” Williams-Derry said.

Today, fracking operations are plagued by bankruptcies, and oil and gas stocks are imperiled by the divestment movement. In the last month, with would-be drivers huddled indoors and Saudi Arabia and Russia each dumping cheap oil on the market to undercut the other, supply so outpaced demand that the price of a barrel of oil briefly fell below zero.

Coal is in even worse shape. Eleven coal companies have filed for bankruptcy since President Trump took office, and the future of the industry looks increasingly dim. Nearly half of all coal plants worldwide will lose money this year, stymied by cheap renewables and natural gas. And the coronavirus isn’t helping. With power demand in a lurch, utilities are leaning more on wind and solar power, which have no fuel costs. On a few days recently, wind turbines supplied more electricity nationally than coal.

The grim reality of fossil fuels has made it hard for coal miners and oil and gas drillers to raise money on Wall Street, so companies have tried to raise capital by selling corporate bonds. Companies pay interest to bondholders until the bond is due, at which point they pay back the full value of the bond.

This is where the Fed comes in. Through its debt buyout programs, the Fed is empowered to buy new bonds issued by any corporation that has a decent credit rating — a score given to companies based on how likely they are to pay their debts. To make sure they only aid companies that were healthy before the coronavirus, they are buying bonds from firms that had a credit rating of BBB- or higher from as of March 22.

“You can’t lend to a corporation that is for sure going to fail. That is not reasonable,” said Wenhao Li, assistant professor of finance and business economics at the University of Southern California. Though, there is no firm line between healthy and unhealthy. “Investment grade BBB- already has a lot of risks,” he said.

Several fracking companies with barely passable credit ratings could rake in billions of dollars, according to an analysis from Friends of the Earth. This includes fracking firm Continental Resources, which saw its credit rating drop just after the March 22 deadline, meaning it is eligible for a bailout, even though it is now a “junk bond” according to two major rating agencies.

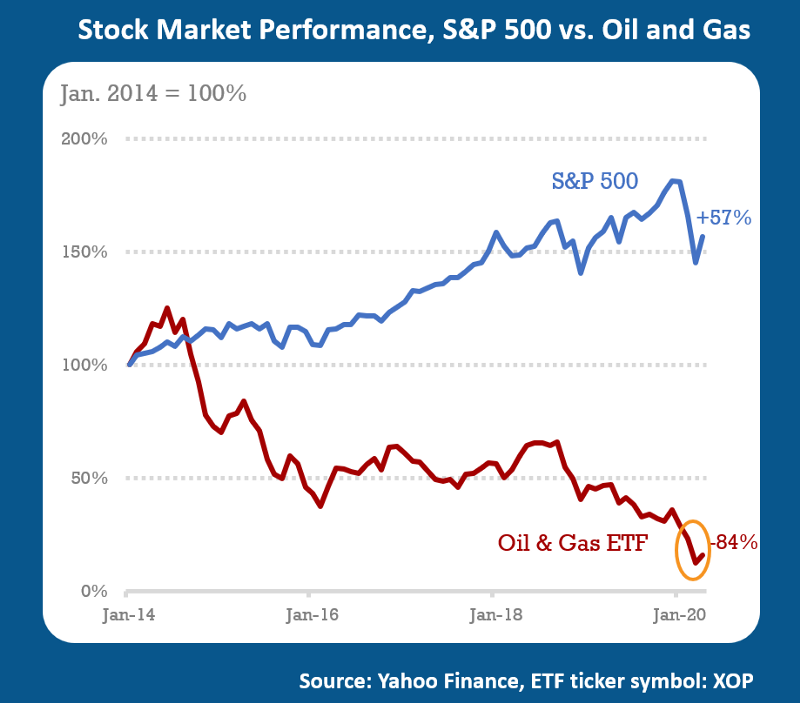

Firms that were rated as junk before the deadline may also benefit from the debt buyout programs. Investment firms will pool together junk bonds into exchange-traded funds or ETFs. The Fed is buying shares of these funds, which is concerning given that energy firms account for the largest share of the junk bond market and they have historically underperformed. One oil and gas ETF has lost 84 percent of its value since 2014, even while the market as a whole grew by 57 percent.

“A better investment strategy than putting money into that ETF in 2014 would have been to take your money, burn half of it, and put the other half under your mattress,” Williams-Derry said. “In 2014, the kooky divestment activist was actually a savvy investor compared to the rest of Wall Street.”

For a long time, investment in the fossil fuel sector, he said, was predicated on a mix of irrational optimism and institutional failure, but with fossil fuel companies consistently underperforming the market as a whole, investors have learned their lesson.

Bank of America, CitiGroup, Wells Fargo and JP Morgan Chase have backed away from coal. BlackRock, the investment firm administering the debt buyout programs, has also told clients that it is also pulling out of coal. And, in his annual letter to business leaders, BlackRock CEO Larry Fink asked companies to disclose climate-related risks, including the possibility that governments would take steps to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement, a fact that should scare oil and gas companies.

Worried that the firm would block aid to fossil fuel companies, a group of Republican senators sent a letter to the Fed asking that BlackRock “act without regard to this or other investment policies BlackRock has adopted for its own funds.” That seems likely, if not inevitable.

Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin told Bloomberg that investment-grade oil companies may be able to secure money through the Fed. He also that he is weighing the creation of a lending program specifically for oil companies that would operate out of the Federal Reserve. The Trump administration has been keen to help the fossil fuel sector, which has tremendous lobbying power in Washington.

As if to illustrate that point, GOP senators recently sent a letter asking the Fed to change the terms of the debt buyout program to accommodate companies who received a poor credit rating before March 22. This would directly benefit Occidental Petroleum, which saw its credit rating drop below investment grade on March 18. Occidental has donated to James Inhofe (OK), Lisa Murkowski (ND) and John Barrasso (WY), all signatories of the letter.

In the same letter, senators also pushed back on the Fed’s requirement that companies that have been assessed by multiple credit rating agencies receive an investment grade from at least two of those agencies. This would benefit coal firm Alliance Resource Partners, which just barely earned an investment grade rating from Fitch, but received a junk rating from Moody’s and S&P. Alliance Resource Partners has donated to signatories James Inhofe and Steve Daines (MT).

“It would be naive to assume that big oil was not trying for as much stimulus money as possible,” said Lukas Ross, a policy analyst at Friends of the Earth. “Those sorts of demands don’t end up on congressional letterhead in a vacuum.”

Ross noted that fossil fuel companies have been contracting lobbyists to work on the coronavirus stimulus, according to publicly available disclosures. These include Range Resources, which, in light of its poor credit rating, should not be able to benefit from the Fed’s debt purchasing program. Though, if the Fed loosens its rules, it could potentially cash in.

On the other side, more than 40 Democratic lawmakers worried about a bailout for oil and gas firms sent a letter to Mnuchin and Fed Chairman Jerome Powell urging them not to include fossil fuel firms in the bailout, writing, “It will only artificially inflate the fossil fuel industry’s balance sheets.”

Asked who they want to see bailed out, Americans overwhelmingly said hospitals, restaurants and small business, according to a new poll from Yale University, George Mason University and Climate Nexus. Fewer than half approved of a bailout for coal companies or oil and gas companies — only cruise lines and casinos earned less support. Crucially, a large majority of Americans, including a majority of Republicans, want to prioritize clean energy firms over fossil fuel firms in the stimulus.

Williams-Derry summed up the challenge of bailing out mining and drilling companies. “This is an industry that has been in financial distress for years now,” he said. “If you’re bailing out a boat that’s already sunk, is that really a bailout?”

Disclosure: Nexus Media is an editorially independent news service affiliated with Climate Nexus, a nonprofit working to improve public understanding of climate change. Jeremy Deaton writes for Nexus Media. You can follow him @deaton_jeremy.