This story is published as part of Covering Climate Now, a global journalism collaboration strengthening coverage of the climate story.

One afternoon in 2012, members of the Lummi Nation called a public gathering on the beach at Cherry Point, near their Bellingham, Washington reservation. They met at the site where SSA Marine was planning to build a large export terminal to ship coal and oil to Asia, a move the Lummi said would violate its treaty fishing rights.

Tribal leaders donning full traditional dress held a ceremony they called “kwel’ho,” meaning “we draw the line.” They lit a huge bonfire and threw in a giant mock check they had fashioned, which was made out to the tribe for “not even millions unlimited.” The message was clear. They could not be bought, and they would fight the export terminal as long as it took.

“They said: ‘no way,’” recalled Eric de Place, of the Sightline Institute, one of the groups battling to keep fossil fuel companies from funneling exports through the Pacific Northwest. “At that point, it became clear there would be no compromise and that we were going to fight them–and others–all the way.”

And fight them they did, for much of the last decade. The Lummi would eventually prevail, but theirs wasn’t the only battle, and they weren’t the only combatants.

The struggle against fossil fuel companies in the Pacific Northwest was a classic David vs. Goliath, though one with countless “Davids,” including activists, small business owners, fishers, Indigenous peoples and others. Each joined the cause for a different reason, but they shared a common goal–preventing their pristine coast from becoming an environmental disaster.

Their opponents were fossil fuel companies digging up coal in Wyoming, pumping shale oil in North Dakota, extracting tar sands in Alberta, Canada, and fracking gas in mountain states. To reach Asia, these firms had to ship their goods through large export terminals in the Pacific Northwest.

“Coal transport is exclusively by rail,” de Place said. “Gas is exclusively by pipeline. And oil project proposals here have taken both forms — rail and pipeline.”

The movement, known as the “Thin Green Line,” aimed to block these exports. They deployed a variety of tactics, including legal challenges, media campaigns and endless appearances at public meetings. They even turned to old fashioned protests, like crowding railroad tracks to halt shipments of fossil fuels.

“We revoked their ‘social’ license by turning public opinion against them. We confronted them on every issue, and wore them down. It was a lot of small victories in small places that added up over time,” de Place said.

So far, they are winning.

“They clearly misjudged how fiercely we will protect this place,” said Brett Vandenheuvel, executive director of Columbia Riverkeeper, a conservation group based in Hood River, Oregon. Through their work, they dealt a critical blow to the fossil fuel industry.

“The movement in the Northwest was a major cause of pushing western coal production into terminal decline, and it has done serious damage to oil extraction, both the fracked oil of North Dakota and the tar sands oil of Canada,” de Place said. “It was the carbon equivalent of stopping at least five Keystone XL Pipelines, and maybe as many as eight.”

The saga began shortly after the financial crisis in 2010. Facing shrinking demand in North America, fossil fuel companies set their sights on Asia’s manufacturing centers, where demand was growing. Coal companies were especially keen to ship their product overseas, as falling prices for natural gas had hurt the market for coal.

“There weren’t enough consumers in North America,” de Place said. “If they wanted to extract more, they needed to find new markets.” This strategic pivot led to a host of bids for new export terminals.

Vandenheuvel won’t forget the day he picked up the phone and heard a tip about one of the earliest proposals, a plan to build a coal shipping terminal in Longview, Washington. He hung up and literally banged his head on his desk.

“Big money, big players, big problem,” he said. “I felt like giving up. How could we fight big coal?”

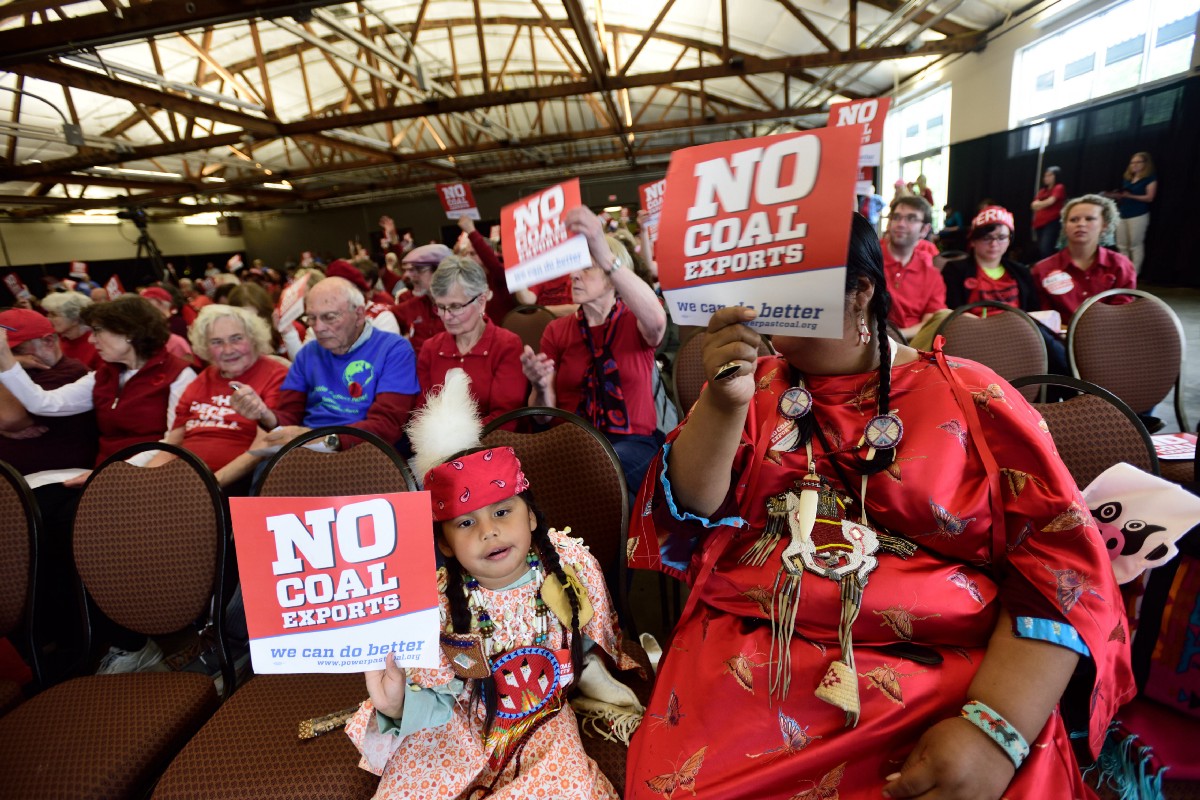

Fast forward two years to 2012. Nearly two thousand people wearing red “no coal” shirts cheered and waved signs as a heavy rain fell on their Longview rally. Undeterred by the downpour, the speakers — including a local doctor, a pastor, a business owner and a Montana rancher — spoke out against coal.

“Surveying the sea of red shirts, a longtime resident of Longview said, ‘I’ve never been so proud of my community,’’’ Vandenheuvel recalled.

In addition to their work in Longview, they organized communities along rail lines, since these towns are most at risk of an accident. That could mean coal spilling from a railcar or an oil train exploding, which happened in Mosier, Oregon, Vandenheuvel said.

“We held community forums and rallies,” he said. “People asked their city councils to pass resolutions opposing fossil fuel projects. Many did.”

Members of the Power Past Coal coalition also submitted extensive written comments to state agencies opposing the export terminal. Several officials said it was the most comments they had ever received. In September 2017, the state’s department of ecology denied a key permit, effectively killing the project.

“The victory was final in 2017, but that rainy day in Longview may have been the moment we truly won,” Vandenheuvel said, recalling the rally.

They deployed similar tactics against Tesoro Petroleum Company’s proposal to build an oil terminal in the heart of Vancouver, one that would receive oil from trains traveling through the Columbia River Gorge and transfer it to ships. In 2013, Vandenheuvel attended a Vancouver port authority meeting — he described it as a “well-planned charade” — where company consultants defended the terminal’s safety.

“Bakken crude oil trains through the gorge: safe. Emissions from huge storage tanks near neighborhoods: safe. Oil supertankers in the estuary: safe. The port commissioners lobbed softball questions and nodded knowingly at Tesoro’s rehearsed answers,” Vandenheuvel said.

If people wanted to understand the danger, he said, they need look no further than explosions such as the Mosier fire, which happened just 10 miles from his house, or a runaway oil train that derailed in Quebec, killing 47 people.

“I was itching to jump up and interrupt this sham process,” he added. “When a Tesoro executive compared Bakken crude to ‘mother’s milk,’ my co-worker — a new mother — was aghast. But we knew this would be a long fight and that Tesoro would win the first round.”

A few years later, however, he stood on stage at a theater in downtown Vancouver alongside the president of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union Local 4, a business owner, a local pastor and two city councilors. All spoke out against the proposal, calling on the state to reject the project.

“The project’s glow of inevitability was fading,” he said. “I believed, for the first time, that we would win.” And win they did. Fortunately, they had an ally in their Democratic governor, Jay Inslee, who rejected the proposal.

“Local heroes in Vancouver, labor unions, neighborhood associations, businesses, faith communities, progressive elected leaders and nonprofit organizations came together with a common vision,” Vandenheuvel said. “And tribal nations, including Warm Springs, Umatilla, Yakama, Nez Perce and Cowlitz, were absolutely critical to this victory.”

Their success depended as much on strategic legal maneuvering, as it did on community organizing that was necessary to turn the press and elected officials against new projects.

“The activists were incredibly effective, not just in one community but all across the region,” de Place said. “I think a major reason why is because they were able to recognize that they shared a common purpose against a common threat. And they were able to share resources with each other.”

But the fights aren’t over yet.

“Right now, there are [several] key fossil fuel export projects in process, and a few others possible, that are of deep concern,” said Matt Krogh of Stand.Earth, a San Francisco-based environmental group. These include projects in Washington, such as a liquefied natural gas plant in Tacoma and a methanol refinery in Kalama, as well as a liquefied natural gas pipeline in Coos County, Oregon. Though, activists believe the “Thin Green Line” will hold as it had before.

“These victories were led by tribal nations, small town librarians, farmers and nurses, and an amazing coalition of nonprofits — all coming together to protect our clean water and our climate,” Vandenheuvel said. “We call ourselves the ‘Thin Green Line,’ but it’s bigger than that. It’s community by community, really envisioning a cleaner future. It gives people hope that we don’t have to keep building this infrastructure. We can do better than this and we are.”

Marlene Cimons writes for Nexus Media, a nonprofit climate change news service.